Jefferson's Vision Fulfilled

The following article originally appeared in the Winter 2010 issue of the William & Mary Alumni Magazine. It is reproduced with permission.

In some ways, the origins of William & Mary's law school can be traced to 1762. That year, a Williamsburg lawyer named George Wythe, one of the most distinguished attorneys in colonial America, was asked to take on a particularly promising recent William & Mary graduate as an apprentice in his law office. Wythe agreed, and so for the next five years, he provided Thomas Jefferson with an extraordinary education that equipped him not only to practice law, but also to provide the intellectual and political leadership that the new nation would so desperately need.

In some ways, the origins of William & Mary's law school can be traced to 1762. That year, a Williamsburg lawyer named George Wythe, one of the most distinguished attorneys in colonial America, was asked to take on a particularly promising recent William & Mary graduate as an apprentice in his law office. Wythe agreed, and so for the next five years, he provided Thomas Jefferson with an extraordinary education that equipped him not only to practice law, but also to provide the intellectual and political leadership that the new nation would so desperately need.

Most aspiring lawyers in colonial America had few options for studying law. There were no law schools in the American colonies. Those persons with considerable wealth could travel to London to study at the Inns of Court. But most young men could not afford such a luxury and so were forced to engage in legal study through an apprenticeship with a practicing lawyer. These apprenticeships were widely derided as an unsatisfactory way to learn the law. In an era with no photocopying machines, many apprentices did little more than copy documents.

Wythe used his mentorship of Jefferson to try something different. Under Wythe's guidance, Jefferson read the standard legal texts of the day and regularly attended court to watch lawyers in action. But Wythe trained Jefferson in far more than legal rules and procedures. Wythe encouraged Jefferson to study the theory of government (both ancient and modern), history, moral philosophy and ethics. Jefferson, in fact, would later develop his own bibliography that an aspiring lawyer should read that covered an astonishing array of topics. Jefferson and Wythe forged a close intellectual and personal friendship, and Jefferson embraced his mentor's zeal for republicanism as the American colonies marched steadily towards independence.

Wythe and Jefferson were both aware that they had been born at an extraordinary moment in human history. John Adams expressed this sentiment in a letter to Wythe in 1776: "You and I, dear friend, have been sent into life at a time when the greatest lawgivers of antiquity would have wished to live. How few of the human race have ever enjoyed an opportunity of making an election of government ... for themselves or their children!" At the age of 33, Jefferson drew upon his years of readings and discussion with Wythe to draft a document - the Declaration of Independence - that gave voice to the strivings of those colonists who sought to establish a republican form of government in the New World in place of the European model of government by monarchs.

Jefferson knew that education was the key to the American experiment in self-government. Whereas monarchies used education, or the lack thereof, to fix each social class in its proper place in the political order, republicanism demanded an educated citizenry ready to engage in the work of self-government. As Jefferson noted, "Enlighten the people generally, and tyranny and oppressions of body and mind will vanish like evil spirits at the dawn of the day."

Jefferson was particularly keen to educate a group of Americans who would exercise what was commonly referred to as "public virtue" - the preference for the greater good over one's individual interests. Jefferson believed that a republican form of government could not survive without the exercise of public virtue, and that such virtue could not be assumed. Young people must be trained to exercise public virtue in the face of the strong inducements of a purely private life.

Jefferson, along with other members of the revolutionary generation, believed that lawyers were particularly well-suited to exercise this public virtue. Historian Robert Gordon has commented on the role of lawyers in the American Revolution and in the establishment of the new nation: "[Lawyers] furnished a disproportionate share of Revolutionary statesmen, dominated high offices in the new governments ... had more occasions than even ministers for public oratory, and were the most facile and authoritative interpreters of laws and constitutions. ... [T]hey seemed to have exceptional opportunities to lead exemplary lives, to illustrate by their example the calling of the independent citizen, the uncorrupted just man of learning combined with practical wisdom."

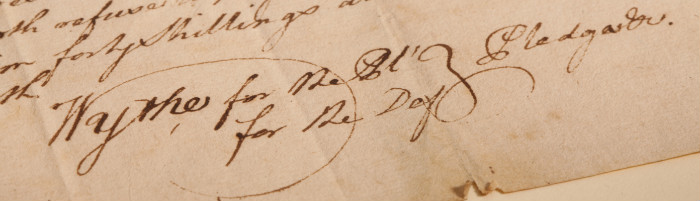

Jefferson became governor of Virginia in 1779, and as part of his gubernatorial duties, he joined the Board of Visitors at William & Mary. Jefferson persuaded the Board to engage in a restructuring of the education offered at the college, which included the establishment of a new professorship in law. To fulfill his vision of training lawyers who would exercise public virtue, Jefferson turned to his old friend and mentor, George Wythe. William & Mary Law School was born with a singular vision of training lawyers who would help the new nation successfully complete its remarkable experiment in self-government.

Wythe began teaching law at the college in January 1780. His students learned the nuances of the English common law, relying in significant measure on Blackstone's Commentaries. Wythe also had his students read the work of contemporary political theorists, such as Montesquieu, and classical writers such as Horace and Virgil. But Wythe did far more.

To supplement this classroom instruction, Wythe introduced the moot court to teach his students oral advocacy skills. The English Inns of Court had first utilized moot courts during the late Middle Ages, but the 17th-century English Puritans had abolished the moot court because the consumption of copious quantities of food and drink that followed the legal arguments was deemed unseemly. Wythe saw the value of the moot court in training his students in the skills of oral advocacy - a highly important skill in 18th-century political culture.

Wythe's second innovation, the establishment of a legislative assembly, served as his central tool for teaching his students the practical art of government. Once a week, Wythe would assemble his students in the legislative chamber of the old colonial capitol building at the end of Duke of Gloucester Street. Schooled in the nuances of parliamentary procedure, the students would debate bills then pending in the Virginia General Assembly. One Wythe student, John Brown, described Wythe's legislative assembly: "He has form'd us into a Legislative Body, consisting of about 40 members. Mr. Wythe is speaker to the House, & takes all possible pains to instruct us in the Rules of Parliament. We meet every Saturday and take under consideration those Bills drawn up by the Committee appointed to revise the laws, then we debate & alter ... with the greatest freedom." Brown was one of eight Wythe students who would later serve in the United States Senate.

Jefferson wrote to James Madison in 1780 to explain Wythe's work: "Our new institution at the College has had a success which has gained it universal applause. They hold weekly courts and assemblies in the capitol. The professors join in it; and the young men dispute with elegance, method, and learning. This single school by throwing from time to time new hands well principled into the legislature will be of infinite value." Wythe explained to John Adams in 1785 that his goal was to train students to take positions of leadership in "the national councils of America."

In fact, Wythe's students would later assume an extraordinary variety of executive, legislative and judicial offices, including president of the United States, U.S. secretary of state, U.S. attorney general, chief justice and associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, U.S. senator and governor. Many others would serve in state legislative assemblies or as judges on the state or federal bench. In fact, if one measures the greatness of a law professor by the accomplishments of his or her students, Wythe was arguably the greatest law professor in American history. Wythe's most distinguished student was Chief Justice John Marshall, the single most important Supreme Court justice in our nation's history. Years later, William & Mary's law school would embrace the name "Marshall-Wythe School of Law" in honor of its most distinguished student and its most distinguished professor.

Wythe continued teaching at William & Mary until 1789, at which point he was succeeded by one of his former students, St. George Tucker. Tucker would, in time, become the most influential legal scholar of the early 19th century, particularly following the publication of his widely read 1803 five-volume annotated edition of Blackstone's Commentaries.

William & Mary has continued the Jefferson-Wythe tradition of training lawyers to pursue the public good - what is now referred to as training "citizen lawyers." Sometimes this work takes the form of public service, as many William & Mary law graduates currently serve in Congress or state legislatures, and as state or federal judges. Many graduates fulfill the citizen lawyer mission in other ways - through leadership in a wide range of public and private ventures that serve the greater good.

On occasion, Harvard Law School likes to claim the honor of being the nation's oldest law school. The claim is unfounded. As the esteemed Harvard Law School Dean Erwin Griswold conceded many years ago: "There can be no doubt that Wythe and Tucker were engaged in a substantial, successful and influential venture in legal education, and that their effort can fairly be called the first law school in America."