A brief description of the Russian legal system. Enjoy!

There are several important aspects that distinguish the Russian legal system from that of the United States. To understand these differences, I've been reading "Law and Legal Systems of the Russian Federation" by William Burnham, Peter Maggs, and Gennady Danilenko. Most of the information below comes from this very well written book.

Law as a Profession

In Russia, there are four types of law schools and they include: 1) university departments of law; 2) state law academies, which are free standing legal institutions; 3) specialized research centers with educational institutions within them (such as the Institute on Legislation and Comparative Law); and 4) private law schools. One can earn a diploma of "specialist in law" after 5 years of study. Essentially, this is both a bachelor degree and a specialization. In contrast, as far as I know, in the US it is not possible to earn a bachelor degree in law and most students in law school have a different undergraduate education. In Russia, the five-year legal specialization is essentially your undergraduate education and most lawyers stop there. Following a few more years of study and a dissertation, a person can earn an optional candidate's degree.

Most graduate the five-year program as jurists and are immediately able to practice law. They are not required to hold a license and thus are not regulated in any way or held to any ethical standards. Another type of legal professional is an advocate, who is much more similar to the US lawyer. An advocate is permitted to represent client in and out of court for a fee. They must apply and be admitted to a Chamber of Advocates, similar to the Bar in the US, both at the federal level and at the regional level. Only advocates are bound by a code of ethics.

Sources of Law

The Constitution: Article 15 of the Russian Constitution states that "the Constitution of the Russian Federation shall have supreme legal force and direct effect, and shall be applicable throughout the entire territory of the Russian Federation."

Federal Constitutional Laws: Higher than ordinary statutes, this special type of law cannot change the provisions of the Constitution or become part of the Constitution. However, Constitutional laws do have the power to displace federal laws. A supermajority of the Federal Assembly must adopt Constitutional Laws for them to become effective.

Statutes: This source of law is the most common and can be either denoted as "federal statutes" or "codes" depending on length and comprehensiveness. When faced with gaps in various provisions, Russian judges have the flexibility to interpret the language broadly. Reasoning via analogy is also permitted in Russian courts.

Presidential Decrees and Agency Regulations: "The President may issue decrees and directives and federal agencies are authorized to adopt regulations. Reflecting their place in the hierarchy of laws, both these sources of law are referred to as "sub-statutory acts" (podzakonye akty)."

Judicial Explanations and Decisions as Sources of Law: Decisions of the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) are binding on all Russian courts. However, to date only the Constitutional Court has cited to ECHR decisions. The Constitutional Court has the power to interpret laws, declare them invalid and also has precedential effect. The Supreme Court has the right to invalidate administrative regulations by declaring them unconstitutional, thus clearly giving such decisions the force of precedent. The decisions of the Supreme Arbitrazh Court are not binding on lower courts, but they are said to form the practice of interpretation and application of legal norms. Lastly, the plenary sessions of the Supreme Court and Supreme Arbitrazh Court also issue "explanations" on substantive and procedural issues, apart from any individual case, which serve as interpretations of the law.

Normative vs. non-normative acts

Russian law distinguishes between normative and non-normative acts. Normative acts include laws and administrative regulations that prescribe "general rules of conduct". They can be further categorized into statutes (zakon) and legislative rules (zakonodatel'stvo). One example of a normative act is a statute indicating that a 5% customs duty applies to all imported vehicles. Non-normative acts are laws and administrative regulations that concern individual situations or specific matters. One example of a non-normative act might be the firing of an at-will employee.

Court System

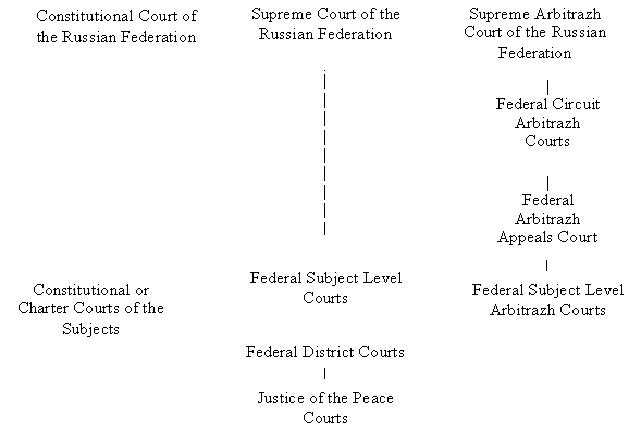

A diagram of the Russian Court System (the term "subjects" implies the component units of the Russian Federation that include republics, regions, territories, etc.):

Constitutional Court: this court not only has the power to review constitutionality of legislation but may also settle other constitutional disputes. Decisions of this court are not appealable.

Court of General Jurisdiction (or Ordinary Court): these courts hear a wide range of civil and criminal cases, and thus are much more important to the average Russian than the other courts. They apply the Civil Code and the Criminal Code, and are governed by the Civil Procedure Code or Criminal Procedure Code depending on the type of case being heard.

Arbitrazh Court: these courts settle commercial disputes. They apply the substantive law set out in the Civil Code and legislation supplementary to it, but have their own procedural code.