Beaches in Koh Kong and IBJ in Pursat

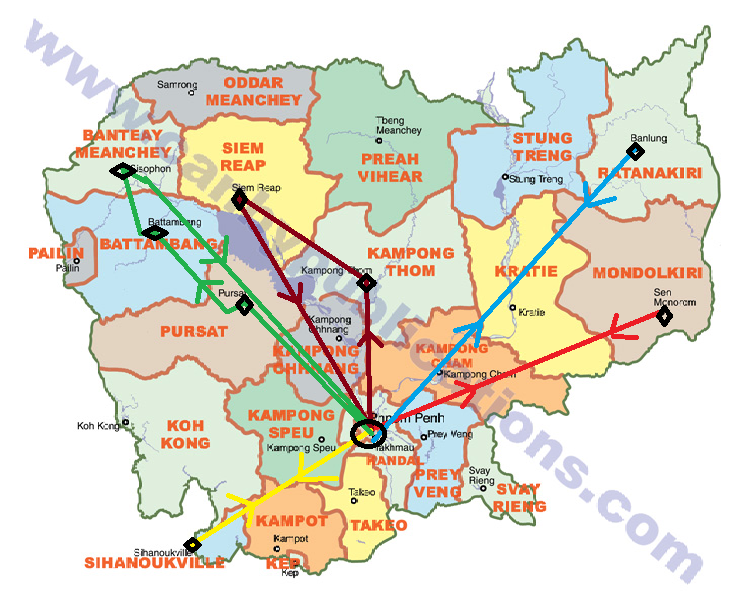

I have traveled to eight provinces since arriving in Phnom Penh: seven with IBJ, beginning with the three I've already written about, Mondulkiri [red], and Siem Reap/Kampong Thom [maroon]; and one with the two other W&M law students interning in Phnom Penh, Kevin Ryan and Atif Choudhury [yellow]. On June 15 the three of us hired a car to take us four hours south to Sihanoukville, a city on the Gulf of Thailand in Koh Kong province. We rented a bungalow in a hotel called the Elephant Garden. The water was cool and clear, and the view from the beach-side hotel restaurant was impressive. The most fun we had was on Saturday afternoon when we each rented a kayak. Although paddling over the breaking waves was much more difficult than we anticipated, after a few tries we managed to get out and around some of the small islands we had seen from the beach.

We returned to Phnom Penh late Sunday night. The next afternoon, I took a bus with IBJ staff for four hours up to Pursat province. Mr. Roth Chanthol, the IBJ lawyer there, met us at the Pursat city DRC. He has been working there for six months and he also covers the neighboring province of Kampong Chang. We talked with him for an hour before dinner to find out how things were going. Interestingly, thing he told us that the second most common type of crime in Pursat, after those that fall under the umbrella of violence to persons (and are most common everywhere), is destruction of property. Under article 410 ofthe Criminal Code, "intentionally destroying, defacing or damaging property belonging to another person," except where minor damage results, is a misdemeanor punishable by six months to two years imprisonment and/or a one to four million Riel fine ($250- $1,000). When I heard that, I assumed that youth gangs with spraypaint cans and time on their hands were behind the problem, but surprisingly most of these crimes are committed as self-help remedies in property disputes.

He gave us a recent example of a man who was married for just twenty days before his new bride left him. Following Khmer wedding tradition, the man's family had built the new couple a house, and the bride’s family had provided the land on which to build. Since the couple's split was less than amicable the relationship between their families was understandably strained, and dividing the property among them proved as difficult as apportioning the blame for the divorce. The village chief organized a negotiation during which the wife's mother agreed to give the husband's family $500 and allow them to tow away part of the house structure; however, she went back on her word and quickly had a wall built around her land to keep them out.

The husband asked the village chief what he should do next and the advice he received was not so sound. The chief told him to retaliate by destroying the wall and removing the entire (unoccupied) house from the property. When he had done this, of course, the woman's family initiated a civil complaint against him which forced the prosecutor attached to the local court of first instance to open an investigation into a possible criminal action. When man received notice of pending investigation he first approached Licadho, a Cambodian-run NGO which specializes in human rights and land rights cases. Because his case did not promise much precedential value, however, that organization referred him to Mr. Roth, just five days before the investigating judge was to hold a hearing. Before starting work with IBJ, Mr. Roth worked for Legal Aid of Cambodia where he only had fourt trials per month; at IBJ, he has at least ten. Therefore, his caseload was already too heavy when he received the referral and he declined to represent the man at his hearing. Since the punishment for destruction of property is fewer than five years, it is not a felony (article 46), therefore the law does not entitle the man under investigation to the assistance of counsel if he can not afford it himself. Mr. Roth promised to keep an eye on the case, however, and especially if the prosecutor charges the man criminally, and Mr. Roth does not have other clients charged with felonies who need his assistance more, then he will represent him in the future.

After we had talked for about an hour, Mr. Roth drove us out to dinner in the back of his pick-up truck. One of the dishes served was vegetables dashed with ants and ant larvae, to add flavor of course. Actually, they made vegetables taste a little bitter in a good way, but, in another instance of mind conquering taste, everytime I looked down and saw the twenty or thirty little black insects, I felt the urge to get up and throw the plate away, like I was sitting on the ground at a picnic and discovered that an army of ants had breached the lunch containers. Of course the Disney song came immediately to mind: "When you look under the rocks and plants/ and take a glance at the fancy ants/ then maybe try a few!"

The next day, Sam and I took a tuk-tuk to Pursat prison on the outskirts of the city to interview a former client who was acquitted this past winter, but found himself back in prison in May on similar charges. Below is the story I wrote for IBJ after our interview:

A handful of prisoners wearing blue jumpsuits play a lazy game of volleyball in the hot sun in the center of the Pursat prison courtyard; another cuts hair in a tiny shack behind the volleyball court; the majority squat idly, hanging their arms through the wire fence that separates their cells from the yard. The more industrious, or, more likely, merely those fortunate enough to have been assigned a task to pass the time, either carry garden tools back and forth across the yard, or take turns tediously pumping water from the only well into plastic buckets. All this takes place outside the window of the hut that passes for an infirmary, where Khek sits across from me on the edge of a stripped-down, wooden bed. An inmate-patient writhes in pain behind Khek on the same bed, groaning and clutching his stomach as another inmate massages a balm into his back. I do not believe I am imagining the disappointment and sadness in Khek’s eyes for being back here after just having been acquitted this past winter.

On May 12, 2012, Khek was arrested on suspicion of stealing a television. He had been working as a caretaker for a local fishery when the television disappeared from a house near his workplace. The owners of that house pointed the finger at him, having long suspected that he and his group of friends were in some kind of gang; but, they were wrong. In fact, Khek was at his friend’s wedding in a village far from his workplace on the day the television was stolen. Many witnesses could have confirmed this, but the police never investigated his alibi after they arrested him at his work the next day. He was interrogated in the local post, then the district post, then the court, where the prosecutor ordered him sent to pre-trial, provisional detention in Pursat prison. He never confessed to the crime, even when threatened with a longer prison sentence.

On December 10, 2012, IBJ organized a large event in Pursat Prison to celebrate Human Rights Day. Ten IBJ lawyers, a dance teacher, a comedian, two music teachers, two American-Cambodian refugees, a spoken word artist and an artist from Phnom Penh gathered in the prison for a three-hour program that allowed the 223 prisoners a rare opportunity to exercise their creativity. Because of this event, most inmates in Pursat prison know about IBJ’s work. Khek, for one, did not know how to contact an IBJ lawyer until he met one on Human Rights Day. That lawyer took on his case and at his trial on January 9, 2013, he convinced the court to acquit Khek, partly by drawing attention to the young man’s eagerness to confront his accuser in court .

When Khek came home to his village, he discovered that one of his friends had in fact stolen the television. Unfortunately, he did not use the occasion as an opportunity to separate himself from that group and paid the price for this failure on May 24, 2013, when he agreed to hold a large sum of money for one of those friends. This friend did not tell Khek where the money came from, but promised that the two of them would use it soon to go on a vacation together. Unsurprisingly, the young man had stolen the money and, after entrusting it to Khek, he disappeared, leaving the latter to face the consequences alone. Sure enough, the police arrived at Khek’s home the next day on a tip and found the stash of money. Now he is charged with theft and once again waits in uncertainty as he shares a small cell with six other prisoners.

Khek is the third of four children and his family visits him once or twice per month. When he gets out of prison he plans either to help his father work construction, or, in all seriousness, become a monk. The latter course is attractive because he is afraid that no employer will trust him since he has been to prison twice, even though the judge acquitted him the first time and circumstances may mitigate the gravity of his second offense. He says that he has met young men in prison who successfully pursued a religious life after serving their sentences.

Mr. Roth Chantol, the lawyer currently working for IBJ in Pursat province, will represent Khek for free when the time comes, but it will take at least six more months before the nineteen-year-old gets back in front of a judge. Recidivist cases like Khek’s are nearly as frustrating for the lawyer as they are for the client, but Mr. Roth knows that in order to make the justice system fairer for all Cambodians he must faithfully and vigorously represent every accused person who seeks him out, not only those with the most tragic story or the most convincing alibi. In order to accomplish IBJ’s goal of building a sustainable legal culture that upholds the rights of all accused, cases like Khek’s are among the more important that IBJ lawyers take on.