IBJ in the Provinces of Battambang and Banteay Meanchey

NOTE: Sequentially, this blog belongs after "Beaches in Koh Kong and IBJ in Pursat."

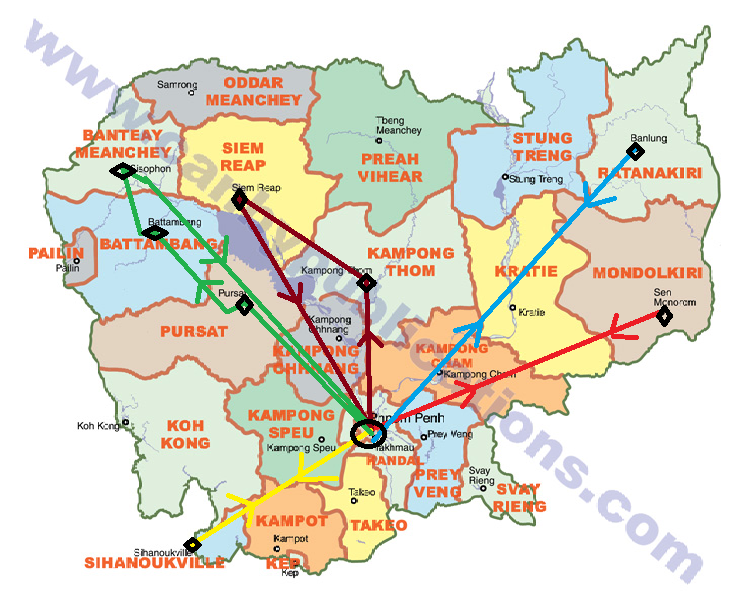

On June 19, the four of us from the Phnom Penh office shared a taxi for a four-hour ride from Pursat up to the DRC in Battambang province [second leg of the green line]. This DRC is unique for two reasons: firstly, it is one of only three IBJ offices located inside a court complex, alongside the offices of the proseutors and judges assigned to this court of first instance (more on the pros and cons of this loction in the story below); secondly, it is the only IBJ office staffed entirely by three women, the lawyer, investigator, and lawyer's assistant.

IBJ Battambang Staff

Battambang Court Complex

That afternoon I interviewed a former client who had been acquitted recently. This is the story I wrote for IBJ:

Sok, a boyish-looking nineteen-year-old man, acted courageously by agreeing to be interviewed in IBJ’s Battambang office because this office is located inside the court complex where, just two months ago, he nearly lost ten years of his freedom. Currently, IBJ is experimenting with offices inside court complexes in three provinces. The hope is that the location will make the organization more visible to the accused and their families; the fear is that the office's proximity to the court might lead the families to associate IBJ lawyers with court officials and, as a result, become more skeptical about IBJ's promise of free legal services because the common belief is that court officials strike backdoor deals with private lawyers, referring cases to them in return for a percentage of the lawyer’s fee. For Sok, returning to the complex raised a different issue: it meant reliving the nightmare of standing inside the courtroom, anxiously waiting for the judge to pronounce his verdict and determine the next ten years of his life. Even having returned this time of his own volition, his eyes still shifted a little nervously around the room. His grandfather made the trip with him. Although elderly and hunched over, the grateful and determined expression on the old man's face told how important he considered it to come and show his appreciation to Ms. Poeung Kalyan and her two assistants, Ms. Ouk Kalyan and Ms. Moeu Sothearet, whose hard work brought his grandson home.

On August 6, 2012, Sok was working for the owner of a cornfield when he heard that, earlier that day, a woman had been killed in a nearby field. Later that afternoon, while he was napping, the police arrived to ask routine questions of everyone in the vicinity of the crime scene. Sok told them that he had not recently been to the field where the murder had taken place; but, the police were apparently unconvinced because at 8 AM the next morning they arrested him with two of his neighbors while the three were outside playing soccer. They sent them to the local police post and interrogated them for an hour on suspicion of aggravated murder. Perhaps because of the gravity of the offense, the police, somewhat uncharacteristically, advised Sok of his right to a lawyer. He was taken to the provincial commissariat, then to the court. There, under the scrutiny of the prosecutor’s questioning, one of the other two suspects blamed the murder on Sok. Although this man was merely an acquaintance, and also a known drunkard and liar, Sok was still shocked to find himself implicated in the murder. As the authorities gathered more evidence, the man’s own involvement in the crime became apparent and he was also charged, but that did not persuade the authorities to discount his accusation of Sok. Thus, Sok spent nine months in pre-trial detention.

His grandfather contacted Ms. Poeung after hearing IBJ’s commercial on the radio. Unfortunately, most of the other prisoners did not know about IBJ, although Sok did notice IBJ’s poster hanging at the entrance to the prison. There was enough food and water to go around in prison, but because of overcrowding he had to share his six-by-eight-meter cell with twenty other people. His family could only afford to visit him once a month. Obviously, Sok’s incarceration took an emotional toll on them, but, on top of that, losing the contribution of his wages strained the family budget, especially as they continued to pay for his two younger brothers’ education.

In all, five people stood accused of the murder, but one had successfully fled to another province and the other, because he was a thirteen-year-old juvenile, could not be detained or given a prison sentence under Cambodian law, even though he had confessed to being an accomplice in the murder. (Code of Criminal Procedure of the Kingdom of Cambodia article 212: “A minor under fourteen years old may not be temporarily detained;” and Criminal Code article 160 makes prison penalties applicable only to minors over the age of fourteen). In lieu of detention, the boy’s family was ordered to pay six million riel, $1,500, in compensation to the victim’s family. The trial was first delayed on February 21, 2013, because a lawyer of one of the accused had been told the trial date too late to prepare his case properly. It was delayed again on April 1, when the court granted the same lawyer a postponement because the thirteen-year-old juvenile, whose testimony he hoped would incriminate Sok, had refused to appear in court. It was delayed for the last time on April 25 because one of the three judges required for felony cases could not be present. (CCPKC article 289: "Three judges of the Court of First Instance shall sit en banc to judge upon a felony.”)

Finally, on April 30, the court declared its verdict: Sok was acquitted. However, in accordance with the code of criminal procedure, he was sent back to prison while the prosecutor considered whether to appeal the judgment. (CCPKC article 381 gives the prosecutor up to one month to decide whether to appeal the judgment of a court of first instance; and CCPKC article 308 mandates that an accused person be kept in detention until the time expires for the prosecutor to file his appeal). Fortunately, the prosecutor only took ten days to decide not to appeal after which Sok was released from detention. The two men accused with Sok, on the other hand, were each found guilty and given ten-year sentences. The man who fled also received a ten-year sentence in absentia.

Sok now takes care of a local farmer’s cows in exchange for the next calf to be born. He has forgiven the man whose false accusation robbed him of almost one year of his life, but he has not forgotten the terror he felt in detention. Even when his family had secured him a lawyer from IBJ, the other prisoners constantly reminded him how unlikely he was to be acquitted. They believed, and had convinced him, too, that he would remain in prison until he was almost thirty years old. He is happy that Ms. Poeung proved them all wrong.

I walked around the city after the interview. Many old French structures in Battambang are still standing, well preserved from the days when Cambodia was a French Protectorate (1867-1949). One of the more famous of these buildings is the former colonial governor's residence.

The next morning, after interviewing the Battambang court president, we hit the road again, this time just two hours in a taxi up to Banteay Meanchey (third leg of the green line). The following morning, we interviewed a judge and a deputy prosecutor of the Banteay Meanchey Court of First Instance before going to the provincial prison to interview the prison chief. Inside the prison, I spoke with two former clients who had both been convicted recently.

The client interview write ups I do for IBJ's website are supposed to illustrate how IBJ lawyers succesfully defend the rights of accused persons, but these two did not have very "successful" stories. The young man actually stole a lap top from the lawyer who was renting the loft above his family's home. The home, moreover, literally looks on the Banteay Meanchey courthouse across the street. Not a wise choice of victim or location. The woman's story was more compelling, and she had in fact received a lesser sentence than the maximum she faced under the law. Here is my write up:

Tevy, a short and stocky twenty-seven year-old woman with a guileless, simple smile will likely spend two more years in Banteay Meanchey prison. Last year, a judge found her guilty of drug trafficking and attempted escape from the police. The first charge was brought against her on July 16, 2012, after her husband abandoned her on the side of the road with his stash of “yama,” a type of methamphetamine distributed in powder-filled capsules, and then drove off on his motorcycle. She has not seen him since then and has no idea how to find him.

A grave misunderstanding between the police and her led to the second charge. During her interrogation, Tevy, unable to sign her name, thumbprinted a confession in which she admitted that she had been traveling with her husband and that he was carrying yama. Afterwards, the police released her. Walking quickly out of the station, she believed she was free, that perhaps the police had even found her husband and charged him instead of her. But, the next day, the same policemen found her at her mother’s house and arrested her again for attempting to flee their custody. According to her, however, she had no intention of running away and even planned to return to the police station that day, on her mother’s advice, to get official papers authorizing her release. Instead, the police sent her to the commissariat and then to the court on July 18.

She had only confessed to being a passenger with knowledge that the driver was carrying drugs, never to either trafficking or absconding, but neither the police nor the prosecutor believed her story. She spent eight months in pre-trial detention before meeting IBJ lawyer Ms. Nop Kunthol on one of the latter’s routine visits to the prison. Before meeting Ms. Nop, no one had informed Tevy of her right to a lawyer or told her about IBJ’s free legal services. At trial, Tevy faced a maximum five-year penalty, but only received three years. Unfortunately, Ms. Nop was unable to get her a lesser sentence than that because the judge would not allow Tevy to offer testimony contradicting her previous, thumbprinted confession. That, combined with a letter from a drug-testing lab affirming that the red pills were methamphetamine, sealed her fate.

Tevy now lives in the female section of the prison with fourteen other women in a six-by-eight-meter cell. The small room even holds three young children whose convicted mothers had no choice but to bring them along. Three days out of every week she takes advantage of the prison’s vocational classes, breaking the monotony of prison life to learn how to tailor. Ms. Nop is still working with her to apply for the King’s pardon, permitted by Article 27 of the Cambodian Constitution. Traditionally, the King considers petitions for pardon four times each year: during the Water Festival, during former King Norodom Sihanouk's birthday, over the Khmer New Year, and on the Buddhist festival of Visak Bochea Daunder. In one more year, Tevy will also be eligible for parole. (CCPKC article 513: “Parole may be granted to a convicted person who has served . . . two-thirds of the sentence in cases where the duration of the sentence is greater than one year.") Tevy does not know whether she will ever see her husband again, nor whether she could ever forgive him for letting her take the blame for his crime. Whether she gets out of prison sooner or later, she only hopes to live with her mother and work as a tailor.

After the interviews we took a five-hour bus back to Phnom Penh. We had been to three provinces in four days, so I welcomed the quiet weekend back in my hotel.