Rattanakiri Province

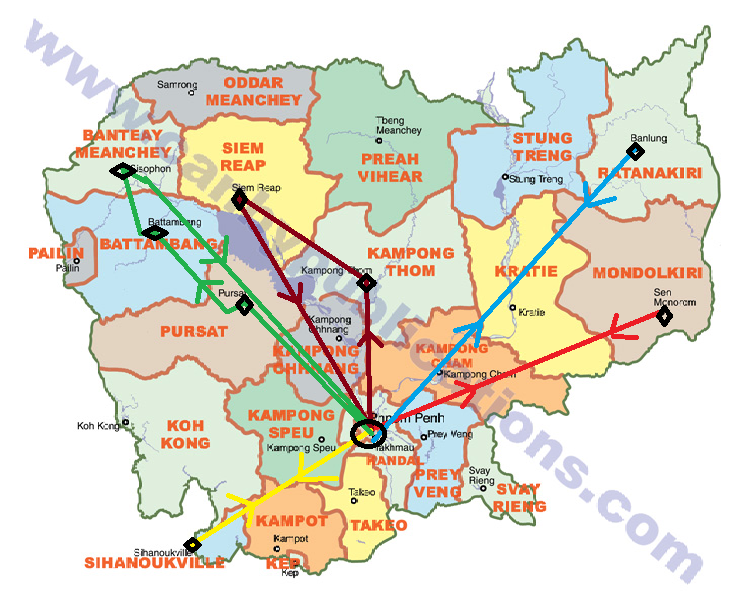

On June 26, four of us from the Phnom Penh office took a minivan northeast to Rattanakiri province [blue]. It was the longest trip I have been on so far and, although minivans travel faster than buses, the ride is far less comfortable than a busride since minivan drivers make sure to pack in their passengers like sardines so that no space in the van that could possibly be used as a seat goes unpaid for. For example, one Cambodian man on our trip was assigned to sit on a plastic footstool next to the sliding door.

Like every trip to the provinces from Phnom Penh, the poor roads and not the distance, 355 miles, account for the duration of the journey. In this case, National Highway 13 is only half-paved for a good 50-mile stretch once you get three hours north of Phnom Penh, and the driver lost a lot of time weaving around potholes that looked more like sinkholes. When we arrived at 4:30, however, I looked around and knew that the ten-and-a-half-hour trip was worthwhile because Banlung, Rattanakiri is also the most beautiful city that I have see here. Like Mondulkiri, it is surrounded by lush forests and green hills, but it is also known for its lakes. The city center itself is much more developed than the pastoral Sen Monorom, Mondulkiri, too.

That first night, I went out to dinner with an IBJ staffmember named Sam and a friend of his who works for a wildlife preservation NGO. Both of them are Cambodian and years ago they spent a study-abroad year together in Germany. I laughed when they told me all the methods they tried to keep themselves warm during the first months of that winter, having never before experienced temperatures below 65 degrees, because I had done exactly the opposite kind of strategizing to keep myself cool during my first month in Cambodia. Boiled lizard was on the menu for the night, but it was followed by pot roast, a welcomed trade-off.

After breakfast the next morning, Mr. Phon Sophoes, the assistant to the IBJ lawyer in Rattanakiri, drove me on the back of his motorbike to meet a former client in a village outside of Banlung. The trip took twenty minutes on a road that meandered over hills, occasionally opening up to views like this one.

Eventually, we turned left down a dirt path and drove up to a row of connected wooden shacks. The first in the row was the home of IBJ's former client. This was the story I wrote for IBJ:

Mr. Phon Sophoes, the assistant to Mr. Mao Sary, who is the IBJ lawyer in Rattanakiri province, takes a left off of the highway that winds through the hills of Banlung city and drives us up a narrow lane between two rows of rubber trees to a series of adjacent wooden shacks. A middle-aged woman is waiting for us there, resting against the side of the first shack as a group of giggling children play around her. Her name is Vany and she is the wife of Paeakey, a former IBJ client whom Mr. Mao managed to keep out of pre-trial detention last year, allowing the husband and father of nine to stay home with his family while he was investigated for murder in connection with a fatal, head-on motorbike collision.

Paeakey is forty-five years old and earns five dollars per day selling the rubber he collects from his small farm of 300 trees. Around 9:30 AM he pulls up the lane in his motorbike. He has been awake since 1 AM, tapping every tree and inspecting the ashtray-sized receptacles in which the liquid rubber drips and hardens. He beckons us to follow him inside his home and we sit on the large table that takes up most of the unit’s space while he splashes water on his face and changes his shirt. Then, he sits and tells us his story.

On the night of October 28, 2011, Paeakey was driving his motorbike home along the twisting highway road with just 100 meters to go. Suddenly, another driver’s headlight shone through the darkness directly in front of him. According to Paeakey, the other driver was going too fast for either of them to avoid colliding and both were thrown violently from their seats. Paeakey lost consciousness and awoke fifteen minutes later as he was being lifted into an ambulance. He had suffered injuries to his right leg and left hand, but otherwise had come away from the crash intact. The other driver was not so lucky and died at the scene of the accident. When the hospital discharged him, Paekey returned to his ordinary life and tried to put the trauma of that night out of his mind. Later that winter, however, the prosecutor summonsed him to the Rattanakiri Court of First Instance to answer questions in a preliminary investigation into the other driver’s death.

The deceased had been a relatively wealthy merchant and, therefore, his family was able to afford a private lawyer in order to pressure the prosecutor to open an official investigation into his cause of death. The investigation uncovered just one piece of mildly suspicious evidence: the medical examiner had noted a strange contusion on the man’s head, which, he hypothesized, might have been caused by another person intentionally striking him. Of course, the other and, frankly, more logical explanation was that the crash itself caused the injury. When Peaekey appeared in court, the prosecutor informed him that the investigating judge would be conducting an inquiry to decide whether to charge him with murder and reckless driving. Paeakey was frightened that he might be put in provisional, pre-trial detention, especially because he did not know how his family would manage without his income.

According to Cambodian law, “in principle” a person under investigation "should remain at liberty," but, ironically, judges more commonly invoke the “exceptional” provision of that same article, which allows them to detain a suspect for such a nebulous reason as to “preserve the public order from any trouble caused by the offense.” (Code of Criminal Procedure article 203: “In principle, the charged person shall remain at liberty. Exceptionally, the charged person may be provisionally detained under the conditions stated in this section.”) For felony investigations, the code authorizes a six-month period of provisional detention, but gives the investigating judge the option to extend the detention up to twelve more months. (The judge may extend the duration simply by issuing “an order with a proper and express statement of reasons.”)

Concerned for his and his family’s future, Paeakey consulted a trusted relative who told him about IBJ. He called Mr. Mao and the latter accompanied him the next time he was summonsed to court, this time by the investigating judge, on March 1, 2012. Mr. Mao was able to persuade the judge not to detain Paeakey, which was a relief to the entire family. Instead, he was allowed to live at home, but he had to return to court five more times for hearings related to the accident. On July 27, 2012, the investigating judge sent his recommendation to the prosecutor: drop the reckless driving accusation, but charge Paeakey with murder. (Code of Criminal Procedure article 246: “When an investigating judge considers that the judicial investigation is terminated, he shall notify the Royal Prosecutor . If the prosecutor considers that further investigative measures are necessary [he] shall return the case file to the investigating judge together with his final submission. The prosecutor may request the investigating judge to issue an indictment against the charged person or to issue a non-suit order.”) The prosecutor followed the investigating judge's suggestion.

At first blush, Paeakey’s being charged with murder at the end of a lengthy and unfruitful investigation looks like a crushing defeat; however, this outcome was actually a minor victory that Mr. Mao himself advocated because the most likely alternative scenario would have required Paeakey to travel an almost impossible distance for him, 500 kilometers south of Ban Long to a hearing in the Phnom Penh Court of Appeals.

According to Cambodian appellate procedure, a royal prosecutor attached to a court of first instance is entitled to appeal any order issued by an investigating judge of that court to the Investigation Chamber of the Court of Appeals in Phnom Penh. Even though the Code of Criminal Procedure explictly exempts the sick and those with “serious reasons” from appearing in person in court--article 309 states: “If the accused cannot be present in the court because of health reasons or other serious reasons, the Court President may order the interrogation of that accused at his place of residence”--in practice, the accused must appear at all hearings. Otherwise, as long as the accused has notice of the proceedings, the Court of Appeals will issue a non-default judgment against him without hearing arguments from him or his lawyer. In a country where ordinary appeals by the accused and convicted are sometimes not even delivered, rarely granted, and always delayed, appealing a non-default judgment is practically impossible. In Paeakdey’s case, if the judge had decided to terminate the investigation without accusing him, Mr. Mao feared that the family of the deceased would pressure the prosecutor to appeal the decision and the Court of Appeals would summons Paeakey to Phnom Penh for a hearing. The Court of Appeals could even decide to continue the investigation itself, in which case Paeakey would be stuck in Phnom Penh for the duration. Therefore, although there was little evidence against Paeakey, Mr. Mao decided that a trial in Rattanakiri was the best option and the investigating judge complied with his suggestion.

Paeakey went about his daily routine for six months while both Mr. Mao and Mr. Phon traveled to his home and the alleged crime scene numerous times, interviewing witnesses and commissioning sketch recreations of the accident from various angles. During the last week of January, 2013, the court informed Paeakey that his trial would be held on February 7. Both lawyer and client were nervous because they were unsure how much influence the victim’s family had over the court. Much to their relief, the three-judge panel acquitted Paeakey. Those of his seven girls and two boys who were old enough to understand the gravity of their father’s situation (they span in age from two to twenty) rejoiced to see him ride up the row between the rubber trees, returning from the court as he had many times before, but this time repossessed of his innocence in the eyes of the law.

(As an aside, although they have been around at least since the French took control of the area in the late 19th century, the increasing prevalence of industrial rubber plantations is one of four main threats to Rattanakiri's environment. The others are: precious metal mines ["Ratanakiri" translated means "Mountain of Gems"], cashew plantations, and logging operations. You can compare Paeakey's small-scale operation that barely provides for his family with the plantation I saw while I was touring the city later in the week.)

Later that afternoon, we interviewed a deputy prosecutor first, then the police chief in charge of misdemeanor cases. Despite the latter's seemingly non-violent job description, I noticed a gun rack with six rifles in the left-hand corner of his office.

After we finished our interviews that Thursday, myself and an IBJ staffmember named Charlene decided to stay the weekend and tour the city before going back to Phnom Penh. I even rented a cheap little motorbike and, that evening, followed the lawyer's SUV to Yak Lom lake. According to Wikipedia, the 157-foot-deep lake covers a 4,000-year-old-volcanic crater. Although I remembered reading a caution in Lonely Planet: Cambodia about swimming in still water, the lake looked clear enough that I dove in off the dock and joined the other thirty-or-so locals and tourists already swimming. As I swam, I was very impressed watching little Cambodian children take turns climbing up the tall trees to pencil-dive off the limbs that bent over the water; I was also a little ashamed for being afraid just to dive off the railing of the dock myself!

The next day, I had promised to take Charlene to some of the local sights listed in Lonely Planet on the back of the bike that I had rented. I'm not ashamed to admit that I woke up half an hour early just to practice turning left and right so that I could accomodate another rider on the back and Charlene wouldn't feel like her life was in danger everytime we got off the highway; Iwas a little embarassed, however, to let the Cambodians who were out and about at 8:30 AM see me puttering around like a sixteen-year-old driver's ed student because I have literally seen five-year-old Cambodian children handle much bigger motorbikes! We saw a couple of nice waterfalls and drove up a steep hill to see a "Reclining Buddha" statue.

After lunch, we had enough energy left for one more destination and decided to check out a place that was marked on the map, "The Stone Field," because it sounded intriguing and mysterious. As we followed the map down the forest road we passed an abandoned tract of land, about the size of a school parking lot, in which we noticed black rocks poking up through the ground. We both joked, "That must be it!" and kept driving, only to discover 10 km later that the joke was on us for reading too much into the name; the "Stone Field" was exactly as advertised. (To be fair, I read later that the site is a landmark because the stones are actually ancient lava rocks.)

Charlene took the bus back to Phnom Penh early the next morning, but I decided to stay an extra day because I wanted drive the 20 miles north to a small village called Voen Sai. There, Vietnamese, Chinese, and Cambodians live together and mingle in a relativelylarge central market. The village sits on a large river on the banks of which live the minority Chunciet people. I wanted to see the Chunciet's cemeteries after reading in Lonely Planet that they carve wooden effigies of their dead and post them like sentries to guard their deceased's gravesites. It hadn't rained that week, so the road was very dusty and I looked and felt filthy when I arrived in the village; but, given the choice between choking on clouds of dirt or slipping down rocky, muddy hills, I counted myself lucky. When I arrived, I hired a motorized canoe to take me 40 minutes down the river to a Chunciet village and cemetery.

When I returned to the the village, I still had a long ride ahead of me.

The minivan company told me to be up by 5 AM the next morning to catch the van. At 5:45, the driver pulled up to my guesthouse and I arrived back in Phnom Penh around 3; if he wasn't punctual, at least this driver was better at navigating the potholes.