Faleminderit - Thank You

Faleminderit- or fa-la-men-deret, translates to thank you in English. There is a shorthand form- "fala" but we were warned against using it in certain circles because it has Serbian connotations. It is also the word that I have been trying to conquer this week in Kosovo. For some reason I have been able to pick up "si jeni?" which is "how are you". But thank you has been a little bit of a battle because I have discovered that I say it so much! My brain throws out the word in English before I can catch myself. I am sure by next week I will have it down and can move on to "good morning".

This week has flown by, and as Abby has commented to me, we have somehow managed to accomplish several big events along the way. Through networking with Dariusz and Ida we were able to meet a German EULEX judge who works in the Kosovo Supreme Court- Special Chambers Division. The man is beyond gracious and after learning that we were both law students invited us to observe his morning hearings on Thursday.

On Thursday morning, after receiving permission from Anton and CLARD, Abby and I made our way to the Supreme Court. It took a little longer than expected to find the building, signs are notoriously ambiguous in Prishtina, but once we did the wonderful people in the building directed us to the room we needed.

Which turned out to be completely empty. We had arrived at 8:50am thinking that the 9am time that the judge had given us was the start time, we were very wrong. After a brief moment of panic and trip around the hallways looking for signs we eventually decided to wait it out. We were awarded in our slightly nervous patience as a law clerk and a couple of petitioners started to trickle in around 9:15am. At 9:30am our friendly judge entered the courtroom and the hearings started. The next two hours were a completely eye opening experience and at times I felt I was looking directly at the heart of the problem with access to justice in Kosovo. The Special Chambers deals with privatization issues within the country. The hearings we observed were all linked to a textile factory that had closed in 1999, due to the on ground situation. Mainly, the loss that people had suffered from unemployment and their subsequent bid to be placed on a list that distributes 20% of the current factory earnings. From what we could tell, the problem seemed to be an odd mix of oversight, poor records, and the general chaos that happens when a country is ravaged by war.

Normally the Special Chambers is a three judge panel, but due to the nature of the hearings and with the acquiescence of the two other judges our German judge was able to hold the hearings by himself. Each petitioner went through the same procedure, they were asked to approach the bench, hand over their identification card, their original workbook, and any pertinent original documentation that they had brought with them. Sometimes this procedure went off with out a hitch, the person would be verified and then the questioning and testimony would start. Other times things broke down very quickly. For an example, at one point the petitioner's name did not match her complaint- after several minutes of translated chaos they worked out that her workbook contained her maiden name. Since our German judge does not speak Albanian or Serbian there are two translators that sit within the court room. As we watched the translator, judge, petitioner, law clerk, and court recorder would fall into a relay pattern that truly boggled the mind. Some of the petitioners really suffered because of it, they did not seem to understand that the lag time between translation and responses were a necessity and often times people would be speaking over each other. Our German judge really exerted a great amount of control over the court and was consistently reigning in the different parties when the communication would start to spin out of control.

A couple of things that I immediately noticed, the majority of all the petitioners represented themselves. There were no lawyers involved with their plea to be added to the 20% list. The other thing I noticed was that in most of the testimony there was an underlying current of hostility against idea that some people were on the list purely because of their ethnicity. It was hard to watch sometimes because of how confused the petitioners were. To a lawyer's ears (or to an upcoming 2L student) the questions that were asked seemed quite simplistic in nature- I was following the line of questioning (and the reasons behind it) with remarkable clarity. But with the petitioners it seemed obvious that something was being lost in translation. When asked to expound on why they did not return to work people would shrug and comment that they were never called or that the secuirty guards would not allow them in- and when prompted on why they thought they were never contacted there were long silences. Followed by the German judge stating that "This is your time in court. It would benefit you and the record that you were as forthcoming as possible." I do not know if the questions were being garbled because of the translation problems or if the culture is so wary of the system that they feel that they cannot speak freely, but either way I hope that all the petitioners will be satisfied that their voices were heard within the legal system.

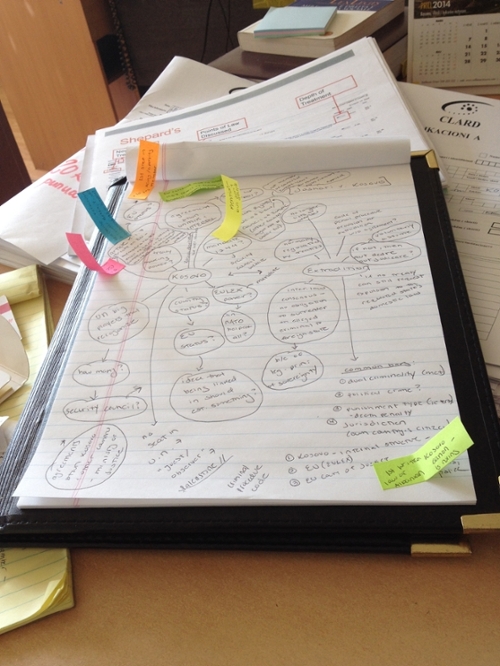

When I returned to the CLARD office after the hearings I started to dive into the three projects that I had been assigned. The first deals with American access to justice, something that I mentioned in my last blog. This access to justice project is sponsored by CLARD and Organization for Security and Co-Operation in Europe (OSCE). The second project that was put on my radar is criminal case involving a man that has been held in custody for 14 years as the courts shuffle him between the Supreme Court and appeals but have never issued a direct verdict on his fate. CLARD is in an uproar about it, as they should be, and have asked another NGO in the city to partner with them taking on the project. The man in custody has given legal permission for CLARD to investigate and file claims on his behalf. The basic plan right now is to take the issue to the Constitutional Court where they hope to set precedent for the country in "detention for a reasonable time"- or the right to a fast and speedy trial. Since CLARD is stil waiting on the other NGO's answer on whether they will take on the case I have been working on the research topic of extradition in Kosovo. The first step was to broaden my general knowledge of extradition and the exact nature of Mandate 1244. To say that the entire issue is a tangled spider's web is an understatement. But the silver lining is that it is SO interesting! For every layer that I peel back regarding the issue two new problems will arise and the entire thing has given me an in depth look on the hardships and struggle that the country of Kosovo deals with everyday. It is hard to function in a shadow land between an independent country and European Union experiment and that fall out from that is beyond normal, imaginative scope.

Anton has been a gold mine of information as I sort through all the paperwork that shrouds Kosovo. In some of our conversations he has referenced how hard it was to survive the war- and this week he told me about the time that Serbian police stopped him and insisted that he was a terrorist. They would not let him leave and detained him (even though the charge was absurd- Anton is not physically capable of being a soldier) until his father could pay a ridiculous amount of bribe money. The things that Kosovars have seen and experienced are beyond compare- they are truly beacons of hope for the future of human rights in the Balkan Peninsula.

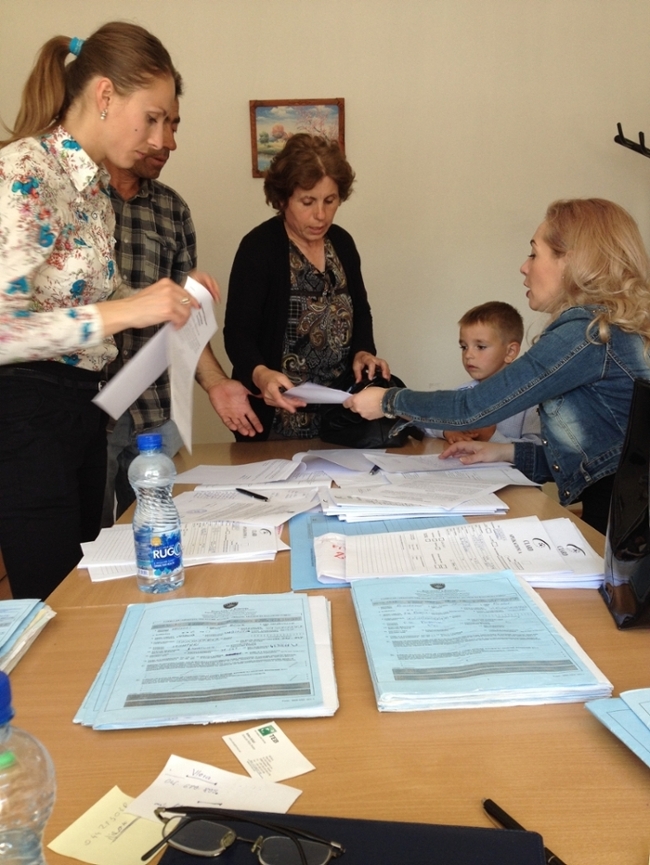

After I had worked on the paper for a bit Anton informed me that he and Nezad were traveling to Prizin for the afternoon. He also told me that I was welcome to accompany two of the female attorneys to their legal aid clinic in a town that was west of Prishtina. This town had produced over 40 cases in the last week. CLARD takes on cases, researches them for a week, and then presents their finds and written complaints to their beneficiaries.

It was truly an amazing experience. When we arrived the small building that CLARD uses was flooded with people. The effect of seeing the CLARD representatives sent the group into a frenzy and Anduena stopped in the middle of the lobby and started shouting in Albanian to stop a rush on the office. After the group had settled down a bit we were able to worm our way into the office. CLARD operates on a tight budget, in part so that they can take on as many beneficiaries as possible. Part this balancing act is getting the Kosovar government to allow CLARD to use governmental offices for a few short hours on various days for free. In this town, the social services office was being used to take on and distribute information to clients. The best part of the situation was that the social service workers in the office are directly integrated into the CLARD process. They help instruct the people on the next steps they need to take with their documentation and often help to shepherd people in and out of the office. The main manager of the office insisted on having a conversation with me- all in Albanian. Through the help of a 14 year old translator I was able to communicate that no, I could not get him a visa to America. It was a great discussion, the man was obviously joking and kept the time that it took distribute 40 cases entertaining as possible. He also gave me a pen before I left the office, I was told it was a gift so that I could sign his visa to America.

CLARD truly goes above and beyond the call of duty when it comes to helping the Kosovar population. They take on all kinds of cases, from property damage to appeals for a human right violation. Part of the reason that I am working on the extradition paper is because CLARD took on a family that had lost their daughter to a violent domestic violence incident. The man who murdered their daughter fled Kosovo with Serbian papers and remains at large- even though at one point Spain had him in custody but refused to extradite him to Kosovo because they do not recognize the country. It has been a wild ride this week, but I remain enthralled by how much work CLARD takes on and the vast amount of quality help they produce for people in need. This upcoming week the roundtables for access to justice start- and I may be called on to present my idea of access to the American justice system. But either way- Abby and I first have to survive our first true cooking experience on our European stove. We're attempting to make spaghetti!

Side Notes:

We experienced our first Scottish barbecue- Ian, the owner/babysitter of the Irish pub hosted a giant ex pat BBQ for the Champion League Final- the football game between Real Madrid and Atletico Madrid. It was a great amount of fun- and they broadcasted the game outside on the side of a building. We also met Nora there, a native Kosovar who is a tireless worker for Kosovo social justice. An amazing woman who literally never stops working. We briefly discussed some of the issues that the Kosovar people have (in Nora's opinion) and I came to the realization that education- something that we Americans take for granted- is a huge difference in believing that social justice is accessible. Nora was telling us how other countries that have experienced bloody civil unrest (like Ireland) carry with them a feeling that they have to protect the future of their children. That even if they do not like the situation they are in currently they will fight to make it work because they do not want their children experiencing the same horrific events that they did. Nora told us that Kosovars do not think like that, they have a short term mind set and do not expect to have deal with long term consequences. This apathy is a major problem- some would say the crux of the problem in elevating Kosovo from a country on training wheels and under the EU thumb to a functioning independent country. Either way, it's food for thought.