Week 8 - An Island of Political Prison

“While we will not forget the brutality of apartheid, we will not want Robben Island to be a monument of our hardship and suffering. We would want it to be a triumph of the human spirit against the forces of evil; a triumph of wisdom and largeness of spirit against small minds and pettiness; a triumph of courage and determination over human frailty and weakness; a triumph of the new South Africa over the old.” — Ahmed Kathrada

Apartheid feels like a word or concept that a non-South African could or should understand, but simultaneously like a word or world hidden behind mist. The weight of it sits inside your chest or throat. It feels like standing on the bow of a boat as it rides into a wall of mist, where the mist covers an island you know is there but you cannot see. It feels like a memory of fear, which makes you feel afraid of seeing what is inside the cloud obscuring the island, even though you know the island is now only one, terrible memory in the ocean of the history of the world. You know all this, but you still feel afraid that you will visit the island and never leave. You feel that somehow the island or the mist could still swallow you, and you would become like the other prisoners who whispered dreams and secrets to cell cinderblocks, limestone quarry rocks, and the sea, wondering if they would ever leave.

________

Nelson Mandela and other prominent political activists who spoke out against apartheid and its regime spent years if not decades in the maximum security prison on Robben Island for their courage and calls for change. Standing in the courtyard near the garden that Mandela discusses in his book Long Walk to Freedom, a place where he and other prisoners would bury books and messages for one another, felt completely surreal. History closed in, and I felt small under the weight of so many days and nights, so many conversations of politics and hope and despair, that incredible people and activists had lived through behind gray cinderblock walls and seafoam green cellblock and window bars.

My friend laughed when I told her; she said that Americans appreciate history to an odd (or dramatic) degree. I laughed in response.

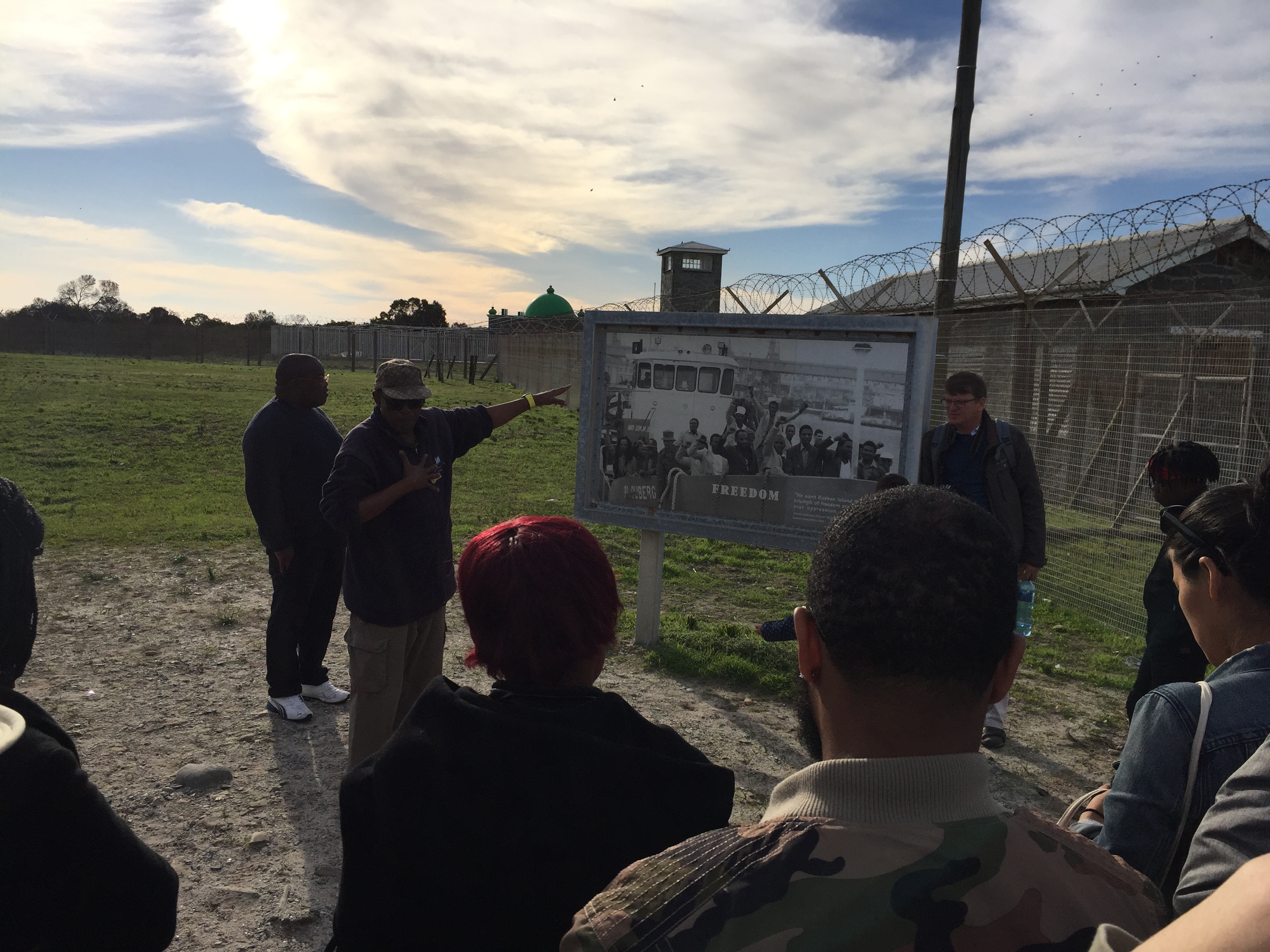

Our tour guide was cheerful at first, and welcomed us in a loud booming voice and a clap of his hands. We stepped off a bus near the maximum security prison cell blocks, and the green-domed Kramat mosque built to commemorate one of Cape Town’s first imams, Sayed Abdurahman Moturu. Our guide led us out onto a hill, and told us about how the tour would proceed; he encouraged us to take our time, and said that the ferry would not leave without us before going back to the mainland. He smiled as some of the visitors laughed nervously.

Then he became serious, and talked about his own imprisonment on the island: He stood tall, looked at each of us in the face, and detailed the charges that had been brought against him, his sentencing and travel to Robben Island, and the five forms of torture he endured while imprisoned (including the use of a single drop of a chemical compound on the top of one’s head that would lead to hours of excruciating nerve and muscle pain). Shocked, all of us stood there blinking at him, unsure how to respond; he clapped his hands again, turned around, and said, “Okay! Let’s go!” without any hesitation.

Outside the cell block where he had stayed, he told us a more hopeful story about how he and the other prisoners would find ways to continue their lives. A cave carved into the wall of the nearby limestone quarry (used for hard labor) was a site for secret meetings and discussions about political strategy, theory, and education. Some prisoners sought to educate others, and would convey books and secret messages to one another. Some prisoners organized and participated in hunger strikes to protest for basic rights, such as the cessation of hard labor, or the provision of beds instead of floor mats, or the provision of skills training and jobs that would put one’s mind to work. Others used comedy as a means to bring a sense of normalcy and release of tension and despair to their fellow cellmates. They would rehearse plays or routines in the bathrooms of the cell blocks early in the morning, and perform for the prisoners in the evening after the day’s work had been done.

Our guide also spoke about some of the initiatives by the national government to bring justice to the families of prisoners who had died on the island: Each visitor to the island was asked by their guide to take a look at the names of people who were still missing. The government had also recruited a special investigative team to locate unmarked graves and return remains to family members, out of respect for funeral rites and other traditions.

We saw Mandela’s cell, as it would have appeared during the majority of his imprisonment. Small and simple, with a floor mat, small wooden stool, and silver wash basin. All I could think about was how the smallness of that space had not really confined or defined this man (and the same for other political prisoners who had been placed in the dozens of other cells in the block). The cell seemed unimpressive after that, and it was freeing, in a way, to realize this.

The views of Cape Town from the island and the ferry were remarkable. The forty-five minute ferry ride was a definite highlight of the trip.