III. National, Permanent, & Independent

Samuel Anthony Alito, Jr., was born April Fools’ Day, 1950. On June 24, 2022, he delivered the Supreme Court opinion that overturned Roe v. Wade. This decision, Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, states that the Court was incorrect when they found the right of a woman to obtain an abortion was constitutionally protected. A long, determined, and partisan war by a faction of conservatives put Justice Alito into the position to write such an opinion. A key battle in that war came down to election administration.

This week’s post is about how Indonesia manages its election system, but its also about how the United States manages its own, and the profound consequences of both. First, I will sketch out the basics of the American election system by tracing the election administration failures of the U.S. presidential election of 2000. Then I will lay out how the Indonesian government administers elections, note key differences, and, of course, share some photos.

The American Election System

The 2000 Presidential Election and Administrative Breakdown

The history of Bush v. Gore is familiar to some, but for most my age, we were too young to understand what was going on, and the collective political consciousness has done a good job sweeping under the rug just how fraught the political and legal battle was. Personally, I believe it was a miscarriage of justice, but that's of no consequence here.

On election night 2000, George W. Bush and Al Gore were short of the 270 Electoral College votes needed to win a presidential election, with Bush at 246 and Gore at 267. The margins were tight in several states, but the result of the national election would come down to the results in one state: Florida, worth 25 electoral votes. Initial returns prompted some media to call the state for Gore, but outstanding ballots revealed a Bush comeback. By the next morning, Gore rescinded his earlier concession to Bush, Democratic and Republican party officials flooded the Sunshine State, and uncertainty took hold.

The day after Election Day, November 8, 2000, Bush’s election night lead of 1,784 votes triggered an automatic machine recount under Florida election law, bringing the margin to 327. The shrinking margin attracted Democratic hopes and Republican fears and launched a weekslong administrative, political, and legal battle between the Gore and Bush campaigns. I am only going to focus on the administrative aspect, but the political and legal aspects of the race are both maddening and fascinating.

If politics is theatre, and campaigning poetry, election administration is chemistry. Any small ingredient can and often does fundamentally alter the composition of the whole. To preview the end of this story, Bush ends up winning the state by 537 votes, or 0.00006% of eligible Florida voters. The margin in the next closest state, Iowa, was 0.3%, and unlike Iowa, this was the decisive state race to determine the presidency, an outcome that would change not only the person but also the party in control of the single most powerful public office in the single most powerful country in the world. One small ingredient could have altered the course of human history.

The frantic stone-turning by the Gore campaign, scrutiny by local election officials, and later investigations revealed a host of administrative problems inherent in Florida’s election system. There is no proof these administrative issues were intentional, but they are the types of issues that are inevitable when elections are staffed, funded, and conducted as they are in the United States.

The most important concept in understanding American elections is how decentralized they are. As with most U.S. policy, there is a divide between the role of the federal and state governments. The U.S. Constitution implicates election administration several times: besides the well-known protections of the Fifteenth, Nineteenth, and Twenty-Sixth Amendments, Article 1, Section 4 gives concurrent authority over elections to Congress and states. In theory, most state laws and regulations can be altered by federal legislation; in practice, this is rare.

The vast majority of actual election regulation is promulgated and enforced at the state level, and all administration of elections is handled by state and local officials. States decentralize to counties, relying on county-level officials and boards to plan, run, and count the results of elections, and counties further divide into precincts that contain the actual polling places and staff with which voters interact.

Only bloodshed, decades of agitation, or catastrophic error has led to serious federal action to regulate elections. The presidential election of 2000 fit into the last category.

The election administration issues that plagued Florida can be grouped as following:

- ballot design

- voting machines

- recounting standards

- partisan, non-professional election administrators

The first, the design of ballots, differed across Florida, as they do in many states, and multiple different ballot designs produced confusion and errors. To name two, “butterfly ballots” may have led to unusually high returns for third party candidate Pat Buchanan in staunchly Democratic precincts, and the “caterpillar ballot,” which stretched candidate names across two pages, resulted in above average rates of voters listing candidates twice, disqualifying their ballots. Second, Florida counties differed in the equipment that voters used to cast their votes, which interacted with ballots in varying ways. Some used more traditional punch-card systems, where the ballot is physically punched through to mark voter intent, and some used an optical scanning machine that reads a marked ballot. The infamous “hanging chad” problem (which doesn’t even begin to encompass all the forms this particular issue took) was a combined ballot design and election equipment issue: the punch-card machine failed to completely punch through ballots that were too thick, resulting in pieces of the ballot (chad) hanging on by one or more of their corners. One can imagine the near infinite ways these problems can interact.

Then imagine recounting them, knowing such thin margins mean each ballot might determine the winner, bringing us to issue three: recounting standards. Because Florida, like most states, conducts recounts in a decentralized fashion, each county is responsible for devising their own standard of review for their results, which means there are sixty-seven counties – sixty-seven potential standards – multiplied by each problem that may be affecting a ballot. Does it matter if a chad is hanging by one corner or two? Three? What size sample of ballots should be used to determine if a full recount is needed in a particular county? If a voter made a mistake on a ballot that would normally disqualify that ballot, but the mistake is plausibly a result of poor ballot design, should the person manually recounting have discretion to infer a voter’s intent? The list is incredibly long, and is in theory hemmed in by the Florida administrative code and the state Secretary of State, but even assuming the guidance is adequate, it takes a statewide effort of poll-watchers and lawyers to enforce the guidance by catching potential mistakes, and only if the adjudication process is fast enough to constitute actual enforcement. These inconsistencies are trivial in a typical election, but in a race of this margin and magnitude, every variable was consequential. For want of a nail, the race could be lost.

These three issues - ballot design, voting equipment, and recount standards - are administrative, but they cannot be externalized from the administrators themselves. Caution is needed here: election officials, including partisans, were one of several safeguards that prevented the Trump campaign from taking the presidency based on fraud. The overwhelming majority are ordinary volunteers fulfilling a vital function and they have been rewarded with violence and harassment. I had the chance to help author a report (see part 4) detailing the threats facing election workers in the wake of 2020 election conspiracy theories. If the reader has the chance to serve as an election worker, they should take it. It is important, rewarding, and educational, and perhaps more vital than ever before.

However, the administrative failures in Florida were nonetheless the result of individual decisions by higher level election officials, which put county- and precinct-level officials in a precarious position. At the highest level, Florida’s chief election official, the state Secretary of State, was at that time an elected position (which is still true of most states). Her name was Katherine Harris, and in addition to overseeing the state's election, she was the chair of Bush’s Florida campaign. Her counterpart in issuing legal guidance to county election boards was Attorney General Robert Butterworth, who served as Gore’s Florida campaign chair. At the top of all governance in the state sat Governor Jeb Bush, the brother of candidate George W. Bush.

Increasing the political tension, the chief elections officer in each county and the accompanying canvassing board are also elected officials, and they are not required to be non-partisan. They are also not required to have any prior experience administering elections, applying election laws, or managing recounts and other election rarities. Given the frequency of elections in the United States, they often obtain some sort of experience quickly, but no amount of learn-as-you-go could have prepared someone for this election, and as fate would have it, Secretary Harris was still in the first year of her term. Public trust in the recount was understandably low on both sides.

There is a long list of administrative failures endemic to the American election system, but these underscore the myriad issues that can arise from running an election and the fractal nature of their consequences. A poorly designed ballot fed into a faulty machine in County A can be reviewed differently from an identical ballot in County B, and the persons reviewing each may have never done so before and be receiving competing guidance from elected officials with a demonstrated interest in the outcome of the race.

Besides the obvious impact these issues can have on elections outcomes, they also provide ample opportunities for political and legal actors to enter the fray. Actors and poets, who should be valued quite highly, are not usually the people needed in a chemist's lab. The ensuring torrent of litigation that resulted in both the Florida and U.S. Supreme Courts issuing multiple orders, staged protests outside key county canvassing boards, and decreased confidence in American elections were made possible by these initial errors. Close margins in such an important election would no doubt have stimulated doubts and challenges regardless, but there would have been no “there there” for good and bad faith actors to latch onto.

Aftermath

In the end, following a protracted legal fight, the U.S. Supreme Court shut down ongoing recounts in Florida in a 5-4 decision, breaking along ideological lines. Gore conceded rather than litigate further, and Bush went on to be certified the winner of the presidential election despite losing the popular vote. He would be re-elected with less, but some, election fanfare in 2004.

In the summer of 2005, Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, a key vote to stop the recount in Bush v. Gore, decided to resign. To replace her, Bush selected an advisor from the Florida recount, John Roberts, but before he was confirmed, Chief Justice William Rehnquist, another majority vote in Bush, died suddenly. Bush withdrew Roberts’ nomination and slotted him into the Chief Justice vacancy. To fill the again-open O’Connor seat, Bush nominated Harriet Myers, a conservative lawyer and then White House Counsel. Deemed not conservative enough by Republicans and a Bush crony by Democrats, she withdrew her nomination.

Then along came Alito, Bush’s third attempt to fill O’Connor’s seat. He was serving on the Third Circuit Court of Appeals, a position to which President Bush’s father appointed him, when he was confirmed 58-42 to the high court. At the time, he was the closest confirmation vote in modern Court history, second only to Clarence Thomas. The number of accidents that had to happen for Alito to be called Justice are astounding, and now seventeen years later, reinforced by two other Bush v. Gore alumni, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett, he has written his own 5-4 decision that will affect generations of Americans. Small ingredients, profound consequences.

The 2000 election changed election administration and law permanently. Judicially, the Bush v. Gore decision remains one of the most confounding cases in election law jurisprudence, a sprawling document that has influenced the role of courts in elections and the standards and remedies involved in electoral disputes. Legislatively, Congress passed the Help America Vote Act (HAVA) shortly thereafter, which did much to address ballot design and equipment problems, and a movement to professionalize the election worker sector has made steady gains in the last two decades. It also established the Election Assistant Commission (EAC) that offers support and grants to states to modernize and improve their election systems. It is one of only two federal agencies, along with the Federal Elections Commission (FEC), that implement national election regulations. Unfortunately, the EAC has no enforcement mechanisms, relying on financial incentives and its clearinghouse of election administration resources to encourage state and local administrators to comply with federal law.

Despite these gains, the damage caused by the Trump campaign’s efforts to overturn the 2020 election will be long-lasting, the volley of recent state election laws may hobble officials, and the COVID-19 pandemic will prevent new generation of volunteers from receiving vital experience. Crucially, high level election officials in the majority of states are still elected partisans, and there is no serious effort to change this. It is possible recent setbacks will generate advances similar to HAVA, but the politics of this moment are decidedly different.

Indonesian Election Administration

Indonesia is far more structured in administering elections. Chapter VIIB of the Indonesian Constitution declares elections must be “direct, general, free, secret, honest, and fair.” (Article 22E(1)). Article 22E(5) authorizes a “general election commission of a national, permanent, and independent nature” to ensure this. The following subsection then grants authority to the national legislature (DPR) and provincial governments (DPRDs) to further regulate elections. (Article 22E(6)). Thus three sources of law for Indonesian elections exist: a concurrent regulatory role for national and provincial governments enforced by a constitutionally mandated agency that “organizes” elections.

In practice, the DPR has used this framework to enact comprehensive election legislation, the most recent of which was passed in 2017. The Organisation of General Elections Law (Law 7, in accordance with Indonesia citation rules) covers nearly every component of elections, but there are key provisions that reauthorize or supplement prior legislation: (1) it determines the composition of the “general election commission” (KPU) called for in the Constitution; (2) it fixes the number of seats in the DPR and sets seat number ranges for provincial and regent DPRDs based on population; (3) it synchronizes all elections to be conducted in the same year; and (4) it establishes two additional election management bodies, the Election Supervisory Board (Bawaslu) and the Election Organizing Honorary Council (DKPP).

The hierarchy of authority between these institutions and provisions is difficult to parse, and the Constitutional Court has not clearly delineated the relationship between the KPU, DPR, and lower level DPRDs. It seems clear that the KPU must exist and be given some authority over the “organization” of elections, but the Constitution is silent on the shape and scope of the KPU, and Law 7 suggests that the DPR retains most control over the KPU. Existing precedent also indicates a DPR statute is prioritized over DPRD regulations, so given the comprehensiveness of Law 7 and the asserted power over the KPU, the DPR exercise primary control over electoral policy, with the KPU as their instrument.

The DPR chose to constitute the KPU with seven members, at least thirty percent of whom must be women (this is mandated by law for all government entities). To select them, Law 7 instructs the executive branch to create a slate of fourteen candidates, from which the DPR chooses the seven KPU commissioners. During their five-year terms, commissioners oversee the entire election system of the country, with province-level KPUs and regent- and city-level KPUs carrying out national KPU orders in one centralized system of administration. In stark contrast to the United States, all KPU elections staff are civil service employees and thus strictly non-political. KPU staff not only administer the elections themselves, but they also manage extensive public databases of electoral information and conduct voter education and outreach efforts.

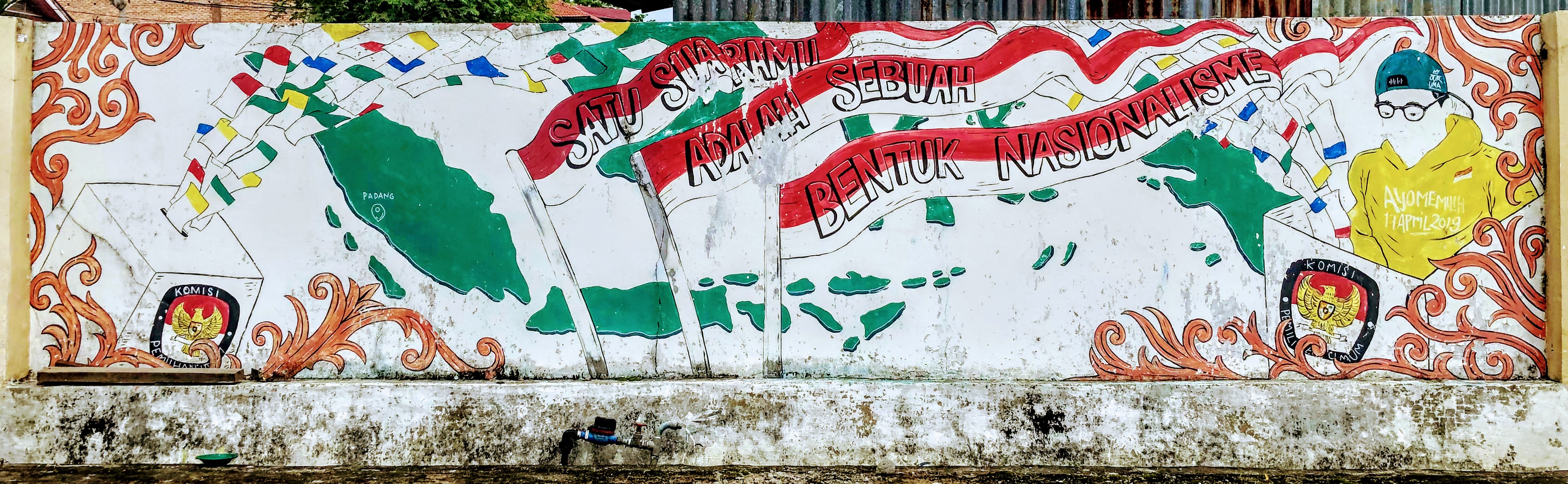

I got to meet with the provincial KPU of West Sumatra, who were conducting a workshop with local KPU boards and neighboring provinces on increasing gender equity in election management in hopes of improving female voter participation.  PUSaKO was in attendance to share their research on the importance of gender inclusivity in electoral work, and I was able to contribute a comparative perspective on American election administration and outreach. Being consummate hosts, they interviewed me on their YouTube channel that is part of a considerable civic engagement program, including an Elections Camp they run for area youth. As a sign of the times, they told me repeatedly that combating disinformation and voter apathy is their top concern after recent elections produced close margins and several political parties, including the losing presidential candidate in 2019, cast doubt on election results and refused to concede.

PUSaKO was in attendance to share their research on the importance of gender inclusivity in electoral work, and I was able to contribute a comparative perspective on American election administration and outreach. Being consummate hosts, they interviewed me on their YouTube channel that is part of a considerable civic engagement program, including an Elections Camp they run for area youth. As a sign of the times, they told me repeatedly that combating disinformation and voter apathy is their top concern after recent elections produced close margins and several political parties, including the losing presidential candidate in 2019, cast doubt on election results and refused to concede.

KPU also faces considerable administrative headaches due to DPR resistance to regulatory reform and adequate funding. Problems of ballot design and election equipment echo the Florida recount, but with fatal consequences. Under Law 7, Indonesian voters must fill out separate ballots for each position. In 2024, citizens will vote on five positions at once: President, DPR, and DPD for the national government, and provincial DPRD and regent/city DPRD members for their provincial and local governments. As many as sixteen eligible parties will be featured on each ballot, with multiple candidates listed below each party for DPR and DPRD members. These ballots are cast with pen and paper, put into a literal ballot box (often made of cardboard), and are statutorily required to be hand-counted by KPU staff. The process is so arduous that in 2019, between 600 and 800 KPU ballot counters died of exhaustion or thirst, and party operatives, eager to dispute the results, harassed counting centers and demanded ongoing tallies.

KPU also faces considerable administrative headaches due to DPR resistance to regulatory reform and adequate funding. Problems of ballot design and election equipment echo the Florida recount, but with fatal consequences. Under Law 7, Indonesian voters must fill out separate ballots for each position. In 2024, citizens will vote on five positions at once: President, DPR, and DPD for the national government, and provincial DPRD and regent/city DPRD members for their provincial and local governments. As many as sixteen eligible parties will be featured on each ballot, with multiple candidates listed below each party for DPR and DPRD members. These ballots are cast with pen and paper, put into a literal ballot box (often made of cardboard), and are statutorily required to be hand-counted by KPU staff. The process is so arduous that in 2019, between 600 and 800 KPU ballot counters died of exhaustion or thirst, and party operatives, eager to dispute the results, harassed counting centers and demanded ongoing tallies.

The DPR has done nothing to address these administrative hurdles, even ahead of the first election in which every elected official in the country will be voted on in the same year, with the five previously mentioned positions elected in February 2024, and provincial governors, regent executives, and city mayors elected in November. It will be one of the largest single-year logistical efforts in the history of democracy, and the DPR have so far failed to capitalize on the ability of the KPU to rollout uniform changes countrywide. If any of the small ingredients present in the Florida recount show up in Indonesia’s 2024 election, it could upend Indonesian democracy and cause lasting damage to the country’s institutions.

The other two election management bodies, Bawaslu and DKPP, are unique to Indonesia. While the KPU administers the election, Bawaslu are something like a rapid response team for voter complaints about KPU conduct. Established as part of a broader anticorruption effort, Bawaslu focuses on actual election fraud and criminal activity by KPU staff. It has a less-than-friendly relationship with the KPU, and has been accused of being a toothless watchdog, or downright unresponsive. Still, members of PUSaKO, KPU, and Andalas University I have interviewed report positive experiences with Bawaslu, and bureaucracy leaders have taken meaningful steps to address corruption concerns and management issues.

Perhaps more effective is the DKPP, which formulates and enforces the Election Organisers code of ethics on the KPU and Bawaslu. The DKPP is composed of members selected by legislatures and “electoral professionals,” and at least one member is appointed by the KPU and Bawaslu together. Ethics complaints against KPU and Bawaslu officials are brought to and adjudicated by the DKPP, and the Constitutional Court has held that the DKPP’s decisions in these matters are final and binding. The DKPP has only existed in its current form for one election, 2019, and so far it enjoys a considerable amount of legitimacy. This will almost certainly be tested in 2024.

Conclusion

Overall, the Indonesian election system faces many of the same challenges as the United States. A people, spanning time zones and topographies, directly elects leaders at multiple levels of government, necessitating considerable planning and manpower to receive, secure, count, and report millions of ballots. Following a tradition of distrust of the federal government, the United States has continued to locate most authority over this process at the bottom of the system, giving states the bulk of the responsibility, who then rely on county and city officials. In contrast, Indonesian leaders have fought to maintain unity and battle local corruption, concentrating most administrative responsibility in one constitutionally mandated agency.

It is unclear to me which system is more resistant to errors. Certainly, the U.S. system has weathered many more elections than Indonesia, and notwithstanding 2000, it has been the participants of elections, not the administrators, that have plunged the country into crisis. Still, the U.S. system is so fragmented, if a quick change was needed and enacted by Congress, it would be difficult to implement and almost impossible to evaluate, as there is no comparable KPU-like body to disperse funds, conduct training, and share information vertically and horizontally to agency counterparts. The nearest election would be the systemwide test, and by then it is much too late. The agonizing rollout of safe voting methods during the pandemic was an unfortunate example of this, as was coordinating thousands of state and local health authorities to share testing data and best practices.

What I believe is true, though, is that Indonesian democracy rests on a constitutional and statutory structure that can deliver free and fair elections if elected officials invest in it. Used properly, the bureaucratic backbone of the KPU and Bawaslu are an incredible resource in ensuring electoral stability and security. West Sumatra’s KPU chief commissioner cannot moonlight as the president’s provincial campaign manager, and standards for ballots, equipment, and recounts can be debated and set before an election, nationally. Election information and materials do not vary regency to regency, partly because national law sets the standard and partly because it is simply unnecessary in a uniform system. Localities are still free to experiment with small changes allowed by law, but a high baseline protects voters who may live in an area with leadership less interested in democratic access. Its "permanence" too is an asset, avoiding the need for volunteer recruitment and high turnover of election workers.

As in America, plenty of Indonesians live under leaders they did not vote for, do not like, and refuse to trust; however, they perhaps needn’t wonder if their leaders were the winners of an election, or a lawsuit. As contentious elections in 2024 draw near, I hope leaders in each country will learn from the lessons of both.