IV. Colonial Scars

For over three hundred years, the Netherlands exercised colonial influence over Indonesia. Dubbed the Dutch East Indies for much of its colonial history, Holland enforced Dutch corporate interests in Indonesia through the Dutch East India Company, which sought to exploit the large collection of island kingdoms and empires for resources, especially spices. The Company’s acquisitions grew into a number of important commercial sectors, but faced with pseudo-governmental responsibilities and security threats, the Dutch government formally absorbed its holdings and territorial claims in 1800, imposing full colonial control. For better or worse, the modern borders of Indonesia are a result of Dutch rule, and the scars of colonialism echo throughout the archipelago, including in Indonesian legal codes.

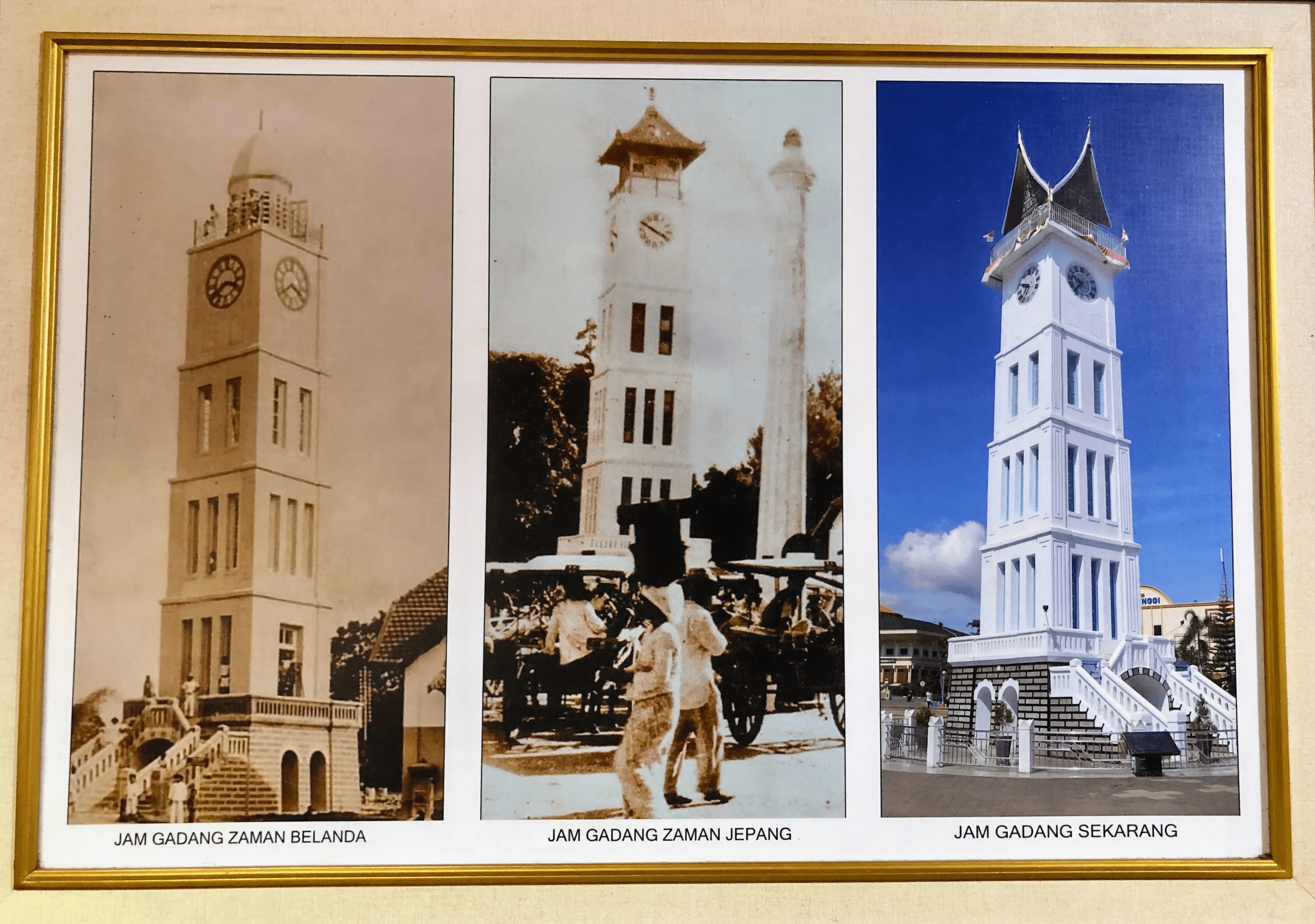

This week’s entry reiterates previous commentary on Dutch colonialism and discusses criminal law that Indonesia inherited from Holland. It also reviews the ongoing impact of anticolonial sentiment and traditional adat law on Indonesian constitutional jurisprudence. Lastly, it features my anecdotal experience with the legacy of the Dutch in Padang and the nearby city of Bukittinggi, complete with photographic evidence.

Independence Days and Competing Sources of Law

This week, the United States celebrates its break from Britain. On August 17, Indonesia will commemorate its 1945 declaration of independence, ushering in the 77th year of freedom from the Dutch and Japanese. With the Netherlands attempting to reassert its authority well into the 1950s, it is a stark reminder of how recent colonialism affected much of the developing world.

Centuries of Dutch control produced an ethnic and economic caste system familiar to many colonized peoples. Compared to some imperial powers, Dutch policy was less focused on “Dutchifying” the indigenous population, with most attention paid to resource extraction and maritime strategic advantage. Nevertheless, Holland’s footprint was far from trivial. Colonists populated Dutch districts of modern day Jakarta, as well as the resource rich islands of Sumatra, Borneo, and Sulawesi. They built European schools, policed areas with Dutch populations, and developed infrastructure for Dutch civilian and commercial use.

As the colony evolved and colonial attitudes in Europe shifted, Dutch leaders developed relationships with certain Indonesia elites, offering them and their families access to the educational, financial, and cultural elements of Dutch society. These elites became key to the administrative apparatus of the East Indies. By establishing an “upper crust” of Indonesians, the Dutch stratified the native population vertically, adding to horizontal divisions across ethnicity, geography, and religion, and concentrating Indonesian wealth and expertise in Jakarta and major cities. These Indonesians later served as the intellectual engine of a growing independence and nationalist movement that united with other local resistance movements and founded present-day Indonesia. These stark class divides persist.

To be expected, the Dutch imported their civil law tradition and code to Indonesia, at first to govern the small population of Dutch colonists and eventually expanded to some parts of the Indonesian society. As a general rule, the Netherlands left Indonesian communities free to use their existing legal traditions (adat, or customary or traditional law), mostly to avoid the administrative quagmire of enforcing a complicated civil code and stoking local backlash.

This was a well-founded apprehension: adat law is an enormously complex and disjointed legal system, dating back centuries and relying on a mix of religious, oral, and ethnic traditions. It is often personalized to local villages, and Western lawyers are ill-suited to understand its highly fluid nature. From an American legal perspective, it might be described as a type of common law unconcerned with stare decisis and lacking a judicial system to organize caselaw. One scholar has also described it as just “as much a process as it is a set of laws.” I might suggest that it is more a system of “justice-making” than a legal system of standards and rules. Regardless, adat is still recognized today by both the legislature and judiciary, but mainly in the areas of land use, divorce and religious customs, and some criminal offenses, and it is steadily supplanted by modern Indonesian statutes and court rulings. Adat’s fate will likely be decided by the divisions between conservative, traditionalist Islamic actors and modernist, nationalist secular leaders that run deep in Indonesian society and politics.

During colonial times, however, adat gradually became a Dutch target in the waning days of Holland’s empire, and it was heavily restricted by the imposition of the Dutch Criminal Code. At first only used in Jakarta, the code was later split into a two-tiered system: the traditional Dutch code to be used for Dutch colonists and a “native” code mirroring the European original but with specific carveouts that both respected indigenous practices and also criminalized certain behaviors that were deemed threatening to colonial rule. Indonesian elites largely accepted this system, as it gave some Indonesians access to a more uniform and consistent justice system, but the separate codes fueled frustrations with Dutch administrators and inflamed traditionalists, especially fundamentalist Muslim sects who viewed it as a threat to Islamic law and culture.

The colonial code served as the primary source of substantive criminal for all Indonesians for decades, until Imperial Japan conquered Indonesia from the Dutch. As part of Japan’s overall war effort in the Pacific, many Indonesians welcomed the Japanese as convenient, if imperfect, liberators. Independence leaders, including future first president Sukarno and vice president Mohammed Hatta, collaborated with the Japanese military, wagering that Indonesia’s future would be better secured in a potential Japanese Asian empire than a region dominated by European exploitation. They also predicted that whatever Japanese ambitions may be, Tokyo’s position in a postwar world would be far more precarious than the centuries of unshaken European control. Beyond these political goals, Indonesian leaders were as much concerned with harm reduction as they were long-term strategy.

It is unlikely that this collaboration made much of a difference beyond sparing elites a degree of brutality. Unlike the Dutch, Japan took over Indonesia in a time of war, and the Japanese campaign in Southeast Asia demanded resources and soldiers. During Japan’s brief hold over the archipelago, hundreds of thousands of Indonesian men were pressed into service and sent to far reaches of the envisioned Japanese empire. Women and young girls were forced into sexual slavery by occupying soldiers, and countless other Indonesians were sentenced to workcamps to produce military equipment and food supplies and to fortify Indonesian islands through a series of forts and underground tunnels. An estimated four million Indonesians died under Japanese rule.

However, independence leaders were correct that Japan’s interference might produce the disruption necessary for a free Indonesia, and Japanese administrators had already convened a working group of Indonesian activists and scholars to prepare for a semi-autonomous nation. With Japan’s surrender to the Allies in 1945, Sukarno and others declared independence the following day, instituting the 1945 Constitution, pronouncing Sukarno the first president, and establishing the new Indonesian government. Populated largely by the elites who were favored by former Dutch rulers, the old criminal code was readopted. It has persisted in large measure to this day.

Efforts for Reform

The original code remains mostly intact, though small amendments have been made and additional criminal laws have been added piecemeal. As with most civil law countries, the code is comprehensive but dense, covering everything from rape and murder to petty misdemeanors. The criminal definitions, standards of proof, and sentencing guidelines are all contained within the single document, and absent common law jurisprudence, courts generally apply the code’s provisions with little discretion.

Reformists have long used the code’s colonial legacy to undermine its legitimacy, but their arguments are often met with additional anticolonial retorts – efforts to overturn criminal provisions evoke Western concepts of individual rights and judicial discretion viewed skeptically by more conservative sectors of Indonesian society. Restrictions on expression, reflective of monarchical deference for government leaders and institutions, run headlong into robust guarantees in the Constitution, but legislative leaders have been reluctant to debate the substance of the code for fear of reducing central government authority and risking draconian amendments by Islamist parties to increase penalties for blasphemy, adultery, and behaviors associated with the LGBTQ, like same-sex cohabitation.

The Constitutional Court, the institution perhaps best positioned to “amend” the Code through judicial review, has also been tepid in its rulings. Acutely aware of its nascent legitimacy, Court decisions on freedom of expression have relied more on refuting “colonial legacies” to invalidate bans on “insults” to government officials rather constitutional promises of free speech and press. And for good measure: legislative attempts to amend the code in 2019 brought both liberal and conservative protestors into the streets across Indonesia, resulting in widespread violence and upheaval. The riots were so intense that legislators indefinitely tabled their efforts.

But the ceasefire has ended. Determined to complete their work, the DPR has renewed the debate over the code and seems determined to pass an amended version this year, even in the face of promised resistance by the public. To do so, DPR negotiators have refused to release a draft of the revisions (which sparked the 2019 violence) and have instead conducted closed-door listening tours throughout the provinces and offered varying statements on the planned amendments.

PUSaKO was tapped as one of several expert testimonies on the draft version, and I got to attend a listening session in the West Sumatra city of Bukittinggi, a vestige of both Minangkabau and colonial heritage. I was not allowed to photograph the meeting, and it was conducted entirely in Bahasa, so I have no real sense of the meetings substance, but PUSaKO members reported that government representatives seemed to take their input seriously. I believe the government is engaging in rather blatant democratic corner-cutting, but I do sympathize with concerns for public order. Americans tend to discount the very real possibility of societal collapse, and a civil code does little in the face of civil war.

PUSaKO engages in other efforts to encourage the DPR to remove restrictions on free expression and the Constitutional Court to uphold individual constitutional rights. As one small example, my colleague, Haykal, and I submitted and had published a Jakarta Post opinion piece arguing that the DPR should learn from the mistakes of previous American sedition laws and the Constitutional Court should look to U.S. Supreme Court jurisprudence to protect free speech. By chance, the day we submitted the piece, a key government spokesman reiterated that bans on “insults” to the president and state institutions would be reincorporated into the code. The Constitutional Court, it seems, remains the people’s best protection from government overreach – I hope they will be willing to enforce the clear constitutional protections Indonesian leaders ratified just two decades ago during the Era Reformasi.

Dutch Remains

Below you can find some older Dutch architecture in Padang, which was a major city in Dutch trade routes. I was happy to see that Padang authorities have repurposed some of the buildings for Indonesian commerce and tourism.