VII. Religion in Law

Every decision by the Constitutional Court starts with the statement: “For the Sake of Justice Based on the Almighty God.”

Every statute and regulation begins: “With the Grace of Lord Almighty.”

The Preamble to the Constitution announces: “By the grace of God Almighty and motivated by the noble desire to live a free national life, the people of Indonesia hereby declare their independence.”

And Article 29(1) of the Constitution states: “The State shall be based upon the belief in the One and Only God.”

This week’s entry is about the role of religion in Indonesian society, politics, and law. As a deeply religious society, Indonesians have gone to great lengths to protect their spiritual traditions. Most, but not all, of these are Islamic, and staunchly conservative Muslim leaders have at times threatened Indonesia’s status as a secular democracy based on the rule of law. However, Muslim and other religious communities played a significant role in the independence movement and the development of modern Indonesia, and with over 85% of the population identifying as Muslim, it is difficult to separate religious motivations from other aspects of life.

Tensions

Indonesian politics suffers from a problem that many Americans would welcome: a lack of party polarization. Voters often have trouble distinguishing between political organizations, partly because they are so numerous it is difficult for parties to stake out an issue set and partly because political leaders often abandon platforms once in office. Before digging into the parties on my own, I asked one of my boss’s, Mr. Charles, which were thought of as more liberal or progressive and which were conservative. He waved his hand. “Not like that,” he said. “Nationalist or fundamentalist.”

Both of those terms are rather charged in the American context, but stripped of their connotations they are helpful for understanding how political parties are organized here, and they inform the sorts of laws and judges they bring to power. Since the founding of Indonesia, most leaders have championed Indonesian nationalism. This is common in emerging nations that need to appeal to a diverse population. These appeals to nationhood typically incorporated socialist and democratic themes of freedom, solidarity, and independence. But from Sukarno to Suharto and into the Era Reformasi, Indonesian leaders never adopted the sort of “state atheism” that Soviet Russia or Maoist China enforced as a means of enshrining the government as god. Sukarno and Suharto certainly didn’t mind being worshiped as rulers, but they were never successful at truly putting the “cult” in cult of personality.

Democracy activists, for their part, have also failed to liberalize religion to the extent other liberal democracies have. A separation of church and state hasn’t been rejected as much as it has been deemed unnecessary. The vast majority of Indonesians pray five times a day, and then urge you to visit the Hindu temples in Bali and the Buddhist monuments in Yogyakarta. They excitedly point out to me the nearest protestant or Catholic church, and then dip into the nearest musholla for afternoon prayer. Religion is just a part of life. In one presentation I did on the First Amendment, several clerks reacted with mild bemusement that Americans would think of freedom from religion as a freedom at all. “That is interesting, but I do not think that is a problem we have here,” one clerk said.

By my read of it, this is largely because nationalism won out for the past 70 years of Indonesian independence, and the quiet secularism that underpins a focus on shared nationhood allowed religious actors to exact concessions without creating deep fault lines. This was helped along by a socially conservative society that is religiously homogenous. Natural island boundaries also conveniently isolate religious minorities, like the Hindus of Bali and the Christians in Papua, and their beliefs were never made serious targets by either the government or the Muslim majority.

But this balance was never truly stable, and in keeping with global trends, present day Indonesia is wrestling with what it means to be Indonesian. Younger generations question the social policies enacted under the auspices of Islam, calls for greater democratization have attempted to use the law and the courts to uphold individual liberties that threaten traditional sensibilities, and opportunistic rightwing forces have forced Islam into the center of political debate over exactly who counts as a true Indonesian. These developments have excited Muslim fundamentalists that see the central government as a threat to their culture and as too comfortable with a global order that has vilified Islamist movements. President Jokowi has courted stronger relations with both the United States, which supports Israel and prosecuted the War on Terror, and China, which actively persecutes Muslim Uighurs. Indonesian students seek entrance to European, Australian, and Singaporean universities, none of whom represent conservative Muslim values or socially traditional worldviews. There’s a sense that Indonesia is forgetting one its bedrock principles: Islam, or at the very least, God. It’s a division that should come as no surprise to an American.

Religion in the Law

One of the clearest indications to how important religious beliefs are to the Indonesian legal community is in the Constitution, and the jurisprudence the Constitutional Court has adopted. The Court is reticent to protect many liberties from government intrusion, even though the Constitution has robust rights guarantees for such things as free speech, press, and assembly. Article 28J(2) of the Constitution includes a stopgap measure that instructs citizens that their rights must may be diminished for the “sole purposes” recognizing and respecting of “the rights and freedoms of others,” or to satisfy “just demands based upon considerations of morality, religious values, security and public order in a democratic society.”

These sorts of exceptions in constitutional interpretation are not exactly novel: U.S. governments infringe upon rights all the time in name of what we might call “morality” or “public order.” No Constitution can adequately balance the demands of the individual and the community through text alone. But the Indonesian Court, has happily taken the exit ramp that Article 28J(2) provides. Justices usually defer to the “public order” provision to uphold government restrictions–from banning protests to criminalizing insults to the president–but they are also a fan of using the “religious values” language as a way flipping constitutional complaints are on their head.

The reasoning usually goes something like the following: a regulation on the decibel level that mosques can use to announce the call to prayer (which happens as early as 4:30am) is challenged on the grounds that it restricts the free exercise of religion. The Court grants standing, as the Constitution guarantees free exercise and the regulation is directly targeting an important practice in Islam. The Court then strikes the regulation down through a combination of Article 28J(2)’s “proportionality” test, which they tend to deploy in two parts: (1) whatever rights are infringed upon by having prayers projected via loudspeaker are defeated by the need to respect the rights of others, and (2) this is a just demand based on the consideration of religious values. When the Court can find a right related to religion, they tend to frame their reasoning as a victory for individual rights; however, if that isn’t convincing, the societal assumption of religious values can carry the day anyway.

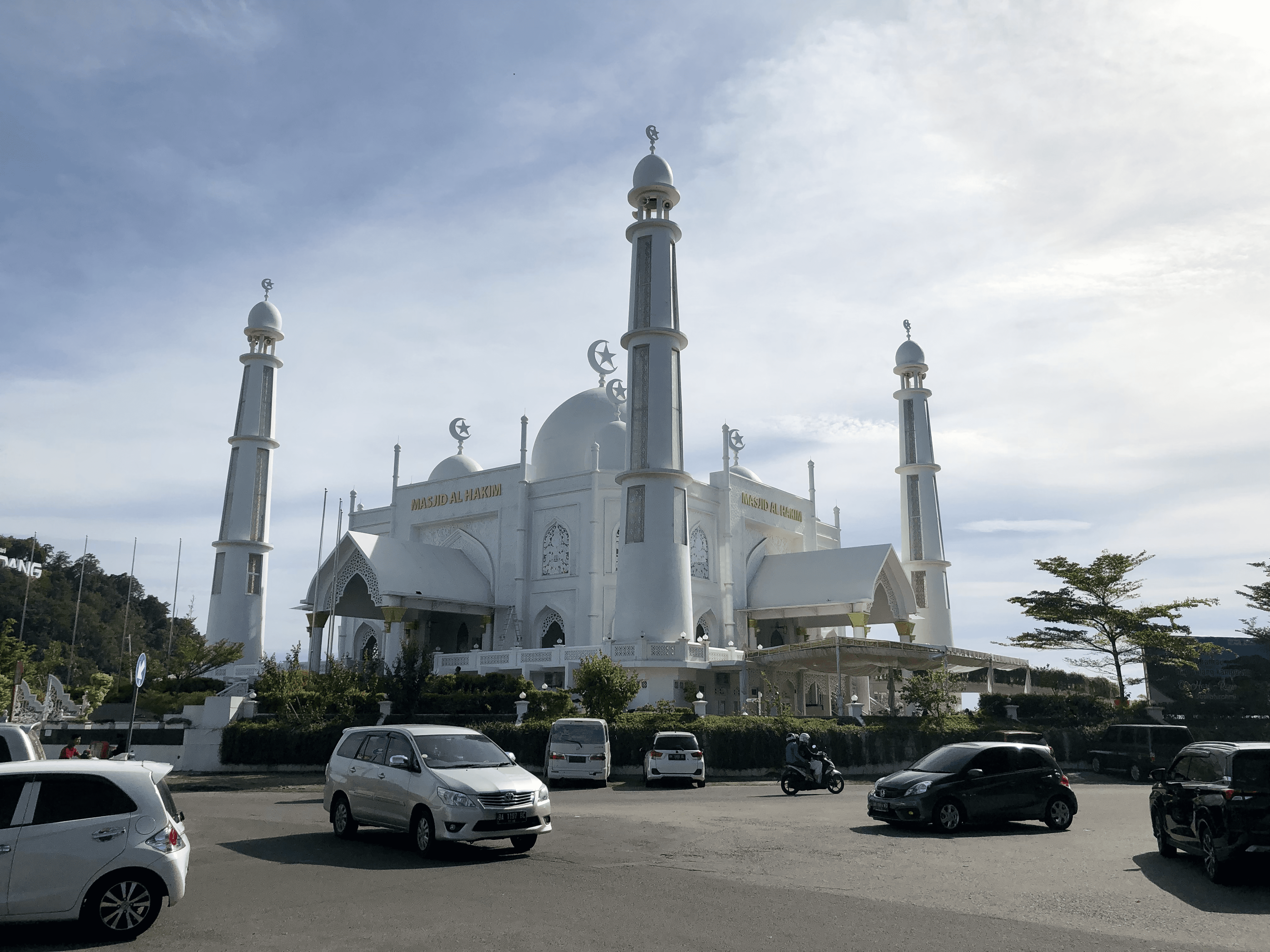

I use this example because I have personal experience with a rather loud call to prayer practice in Padang. I want to be careful here: I am neither religious nor Muslim, and I am a guest here. I did not grow up with the call to prayer integrated into my daily life, and there’s a beauty to hearing the call float through the city and the community engaging in a common practice. I am also confident Indonesians would find many cultural practices in America difficult to adjust to. However, there are times when the regulation mentioned above is probably a good idea. While I was in Padang, I stayed near the beach in a business and nightlife district. There were a good number of homestays and hotels and many residences. Right at the center of this area stands a large new mosque. It is stunningly built and attracts tons of worshippers. It also has four minarets with three extremely large megaphones atop each.

If you are anywhere near the mosque, you basically cannot escape the sound, and as mentioned, one of these is around 4:30am, with another between 5:30am and 6:00am. I am not a light sleeper, I wore earplugs and took melatonin, and I am pretty exhausted each day, and the call will jar you awake anyway. And since this is a newer mosque with a sort of celebrity status, there are countless other special prayers that are said with no particular schedule, so it is difficult to plan around.

At first I kept my observations to myself, but eventually I couldn’t help but ask my homestay owner if he gets complaints from people. He laughed and touched his hand to the top of head: “So bad for business!” I asked some PUSaKO members, all of whom are practicing Muslims, if this ever gets discussed. They told me that when regulations have been passed, people do not follow them, and the local governments do not enforce them. Fair enough.

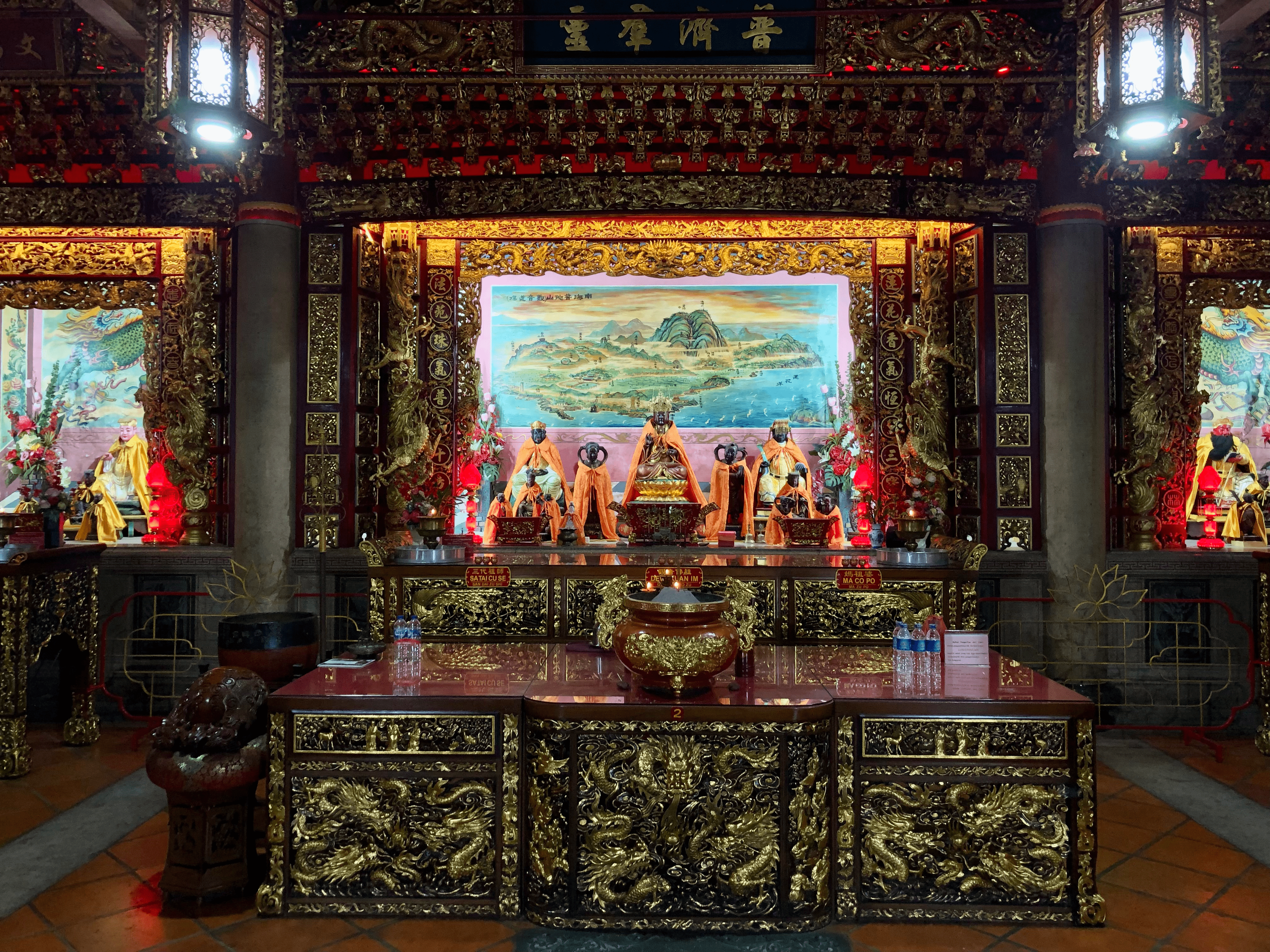

Several weeks ago, I went to Padang’s Chinatown. Chinese communities are widespread in Indonesia, and many can trace their heritage back hundreds of years. Most Chinese-Indonesians are Christian, Buddhist, or Taoist, and often a blend of all three. I was a bit haggard, but I wanted to do something cultural and quiet, so I visited a Taoist temple and sat with a man who helps maintain the grounds. While he was meditating, the call to prayer sounded through the city, and it occurred to me just how all-encompassing Islam really is, even for Indonesians who may not practice it. Knowing I was sitting there, he opened his eyes, chuckled, and said “very loud.” I grinned.

I have a strong suspicious that if a religious minority voiced a constitutional or political concern about this, their claim would fall on deaf ears. That’s not because the majority religion is Islam; it’s because Islam is the majority religion. The presumption of the legal system is that religion is core to civic life, and for the vast majority of Indonesia, that means Islam.

Indonesia has bigger problems than noise pollution, and again, the call to prayer is a longstanding practice with deep cultural and religious significance, but it is an example that captures how a religious custom can subvert the rule of law and constitutional interpretation. It is also not the only area of law where religious sentiment seems to trump all other considerations. Pornography is banned. Non-married couples cannot live or even stay in a rented room together. At my homestay, there is a specific process for demonstrating your marriage license if you want to stay together. The LGBTQ community is routinely harassed and discriminated against with few protections. And then there’s the blasphemy law.

Laws against blasphemy have been at the center of two prominent examples of how powerful religious leaders are in Indonesia. The first was a Constitutional Court ruling in 2009. The second was the imprisonment of the former governor of Jakarta. In Constitutional Court Decision 140/PUU-VII/2009, the Court made three significant statements: (1) Indonesia recognizes “Almighty God” as the “primary principle” that organizes the state; (2) there is no such thing as separation between the state and religion; and (3) the Constitution does not allow groups to press for freedom from religion or “offend or discredit” religious texts and teachings. One clear implication of this is that atheism is not protected, and citizens and political groups will not have criticisms of religious traditions protected by free speech.

This is not just posturing by the Court: high ranking officials have been jailed for supposedly disparaging religion. In a remarkable turn of events, current President Jokowi won the presidency in 2014 while he was serving as governor of Jakarta. At that time, national and regional elections were not simultaneous, leaving the remainder of Jokowi’s term as governor to be completed by his lieutenant governor, Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, who was known by his nickname Ahok. Ahok was Chinese-Indonesian and a Christian, as well as a close ally of Jokowi. While seeking reelection to a full term, his background and religion made him a target for more conservative religious and political leaders, some of whom denounced his promotion to governor as an affront to Islam. Relying on Qur’anic teachings that non-Muslims should not lead a major Muslim country, Ahok’s detractors stoked anti-Chinese and Muslim fundamentalist sentiment.

Ahok responded by saying the Qur’anic citations were being used to deceive voters, and it ignited a political and legal firestorm. Ahok was pilloried in the media and isolated by his party. Eventually, the largest protest in Indonesian history spilled into the streets of Jakarta, with calls for Ahok to be impeached and lynched. Ahok lost the election and was charged with blasphemy. A district court sentenced him to two years in prison, and his appeals were denied. President Jokowi did nothing to defend him. It is no wonder that during his own reelection campaign, Jokowi dropped his vice president and brought on a Muslim cleric to shore up support from conservative Muslims.

Religion is always in dialogue with other forces in society, so it can never be neatly divided from individuals’ other motivations in life. No doubt the reaction to Ahok’s statements were a reflection of racism toward Chinese-Indonesians, and the Court’s ruling on blasphemy factored in the Court’s need for legitimacy as a young institution in a nascent democracy. But whatever the totality of the situation may be, religious demands tend to win, even before a government and court that routinely tramples on individual rights. This does not bode well for a society undergoing tremendous change, many of which are sure to conflict with traditional religious priorities.