VIII. Library, the Lion City, Indonesia's Neighbors

Library and Presentation

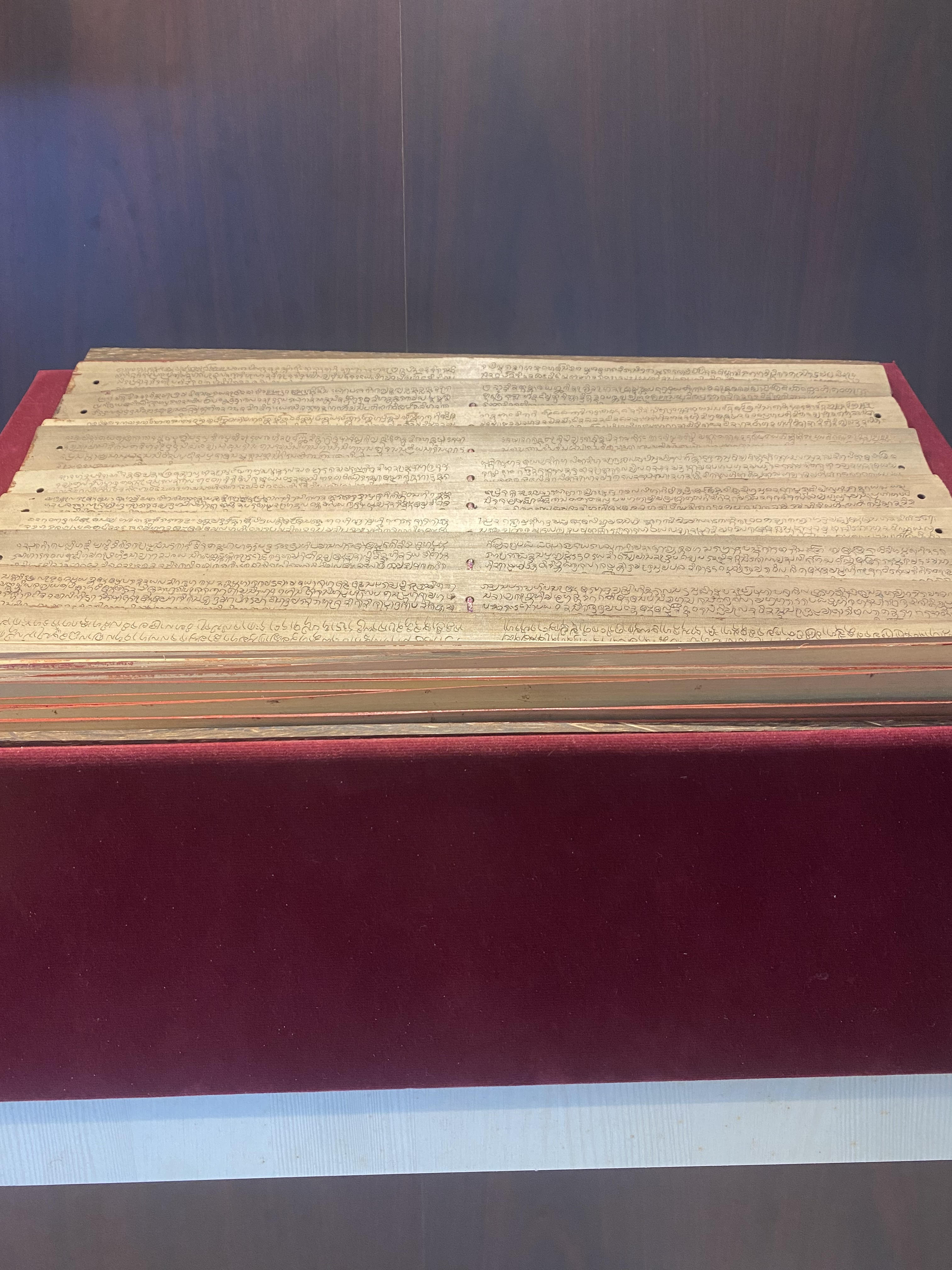

On Tuesday, I was able to join a field trip to the stunning National Library of Indonesia, a 27 floor building completed as a cultural endeavor in 2013. On the top floor, I was able to visit an observation deck overlooking Merdeka Square and play an angklung traditional percussive and melodic instrument made of bamboo tubes. I was also able to see the manuscript collection, including bamboo and wood scrolls in Sundanese script and illustrated codices depicting the adventures of ancient princes.

building completed as a cultural endeavor in 2013. On the top floor, I was able to visit an observation deck overlooking Merdeka Square and play an angklung traditional percussive and melodic instrument made of bamboo tubes. I was also able to see the manuscript collection, including bamboo and wood scrolls in Sundanese script and illustrated codices depicting the adventures of ancient princes.

Then on Wednesday, I gave a presentation on judicial independence and funding of the American judiciary to over 60 people from the Constitutional Court participating over Zoom and in person. The presentation ended up lasting almost two hours after their many thought-provoking questions. I was also finally able to meet some of the Constitutional Court staff visiting America as part of the educational program, some of which were able to join over Zoom while wrapping up their program.

Indonesia and its Neighbors

I am currently in Singapore, so I figured I would digress a little to talk about Indonesia’s relationship with its neighbors Malaysia and Singapore.

Malaysia was founded in 1963 after over a decade of decolonial maneuvering, confusion, and anti-communist bloodshed, combining the Federation of Malaya, Singapore, North Borneo, and Sarawak. The Agreement was engineered mainly by the British and the Malayan Federation, and merger provoked a split in the Singapore People’s Action Party (PAP), which held a majority in the Legislative Assembly supported integration with Malaysia. A PAP-sponsored referendum, none of the options for which excluded integration altogether, elected integration with Malaysia on the condition Singapore maintain autonomy in healthcare, education, labor, and language policies. The Agreement also called for referendums in North Borneo and Sarawak on joining Malaysia. The Sultan of Brunei refused to sign the Malaysia Agreement, following an anti-merger revolt suppressed jointly with the British.

Indonesia during the Guided Democracy of President Sukarno questioned the legitimacy of the Malaysia Agreement. Sukarno, having freshly removed the Dutch from Dutch New Guinea/West Irian in 1962, considered Malaysia a cynical British project to keep a toehold in the region and suppress the decolonial goals of kindred Malay-speaking peoples on the other side of a border negotiated during the colonial period between the British and Dutch governments. Indonesia insisted on holding off the formation of Malaysia until a UN mission reported on support for integration in North Borneo and Sarawak, which declared independence from the British as part of Malaysia in August 1963 before the UN delivered its findings. Malayan Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman refused to postpone integration in the face of Indonesian demands and announced the formation of Malaysia on September 16, 1963.

Indonesia ended diplomatic relations with Malaysia and engaged in infiltration and combat along the border through Central Borneo. Malaysia, a nation at the time of only some 10 million people faced against a neighbor with over 100 million people, sought the support of the British and Australians in defending North Borneo and Sarawak. The conflict dragged on and Indonesia even suspended its relationship with the United Nations in 1965 after Malaysia was elected as temporary member of the Security Council. The confrontation ended in 1966 when General Suharto replaced Sukarno in dealing with foreign counterparts. Indonesia under Suharto quickly repaired relations with Malaysia, eventually becoming a founding member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) with Malaysia, Thailand, Singapore, and the Philippines in 1967.

“Little Red Dot”

While the confrontation with Indonesia was still unfolding, Singapore’s relationship with Malaysia was falling apart. Two main points of tension were revenue sharing and trade union agreements and ethnic policies. The Malaysia Agreement stipulated that 40% of state revenue generated in Singapore would go to the federal government, and obligated Singapore to provide development loans to North Borneo and Sarawak. The other end of the bargain was that Singapore would participate in a trade union on equal terms. Singapore alleged that Malaysia dragged its feet on the trade union by continuing to impose discriminatory tariffs.

The majority in the Malaysian federal government at the time belonged to the United Malays National Organization, which Singapore accused of putting forward policies that discriminated against Chinese and Indian Malaysians and privileged Malays and Borneo indigenous peoples. Racial and ethnic tensions became explosive in 1964, fanned by political leaders calling to crush their perceived adversaries, culminating in race riots in Singapore in 1964. The PAP publicly attempted to salvage Singapore’s status as a member, but Singapore was expelled from Malaysia on August 9, 1965, which will be celebrated next Wednesday as Singapore National Day.

Singapore has a Westminster-style parliamentary government. Since independence, the parliament has been dominated by the PAP, and Singapore was guided by Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew until 1990. Singapore has focused on policies for improving productivity, social cohesion, and creating a friendly business climate. English is promoted as one of four official languages, along with Malay, Singaporean Mandarin, and Tamil, as a unifying tongue for these multiple ethnic groups. English also connects Singaporeans to the dominant language of international commerce. Lee Kuan Yew stated that he sought to avoid fragmentation into mutually hostile ethnic parties, touting this as a lesson hard learned from the era of union with Malaysia. Most people live in housing purchased from the Housing Development Board, which employs ethnic quotas under an Ethnic Integration Policy aimed at increasing exposure and friendly relationships between ethnicities.

has been dominated by the PAP, and Singapore was guided by Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew until 1990. Singapore has focused on policies for improving productivity, social cohesion, and creating a friendly business climate. English is promoted as one of four official languages, along with Malay, Singaporean Mandarin, and Tamil, as a unifying tongue for these multiple ethnic groups. English also connects Singaporeans to the dominant language of international commerce. Lee Kuan Yew stated that he sought to avoid fragmentation into mutually hostile ethnic parties, touting this as a lesson hard learned from the era of union with Malaysia. Most people live in housing purchased from the Housing Development Board, which employs ethnic quotas under an Ethnic Integration Policy aimed at increasing exposure and friendly relationships between ethnicities.

Singapore, unlike its neighbors, of course has little in the way of natural resources such as timber, mineral deposits, oil and gas, or agricultural land. The city state also cannot generate adequate supplies of water independently. Water agreements guaranteed as part of the Separation Agreement ensure that Singapore can draw 250 million gallons of untreated water per day from the State of Johor in Malaysia and oblige Singapore to return a 2% as treated water. Johor has wanted to increase prices; Singapore has rebutted that the cost of treating the water is immense. A 1962 agreement will expire in 2062. Singapore has also conducted major land reclamations projects, which requires the importation of sand. Indonesia recently lifted a ban on sand exports, which was undermined by illegal dredging, much of which is sent on barges for reclamation projects in Singapore.

Singapore has compensated for these disadvantages in a short time by becoming a hub of financial services and global commerce, promising firms an educated and socialized workforce and friendly and predictable governance. During the Indonesian reformasi period at the end of 1990s, Indonesian President BJ Habibie made a stir in Singapore by referring to the country as a “little red dot,” noting the country’s appearance on maps of Southeast Asia, which Singaporeans have embraced defiantly. Habibie later insisted he meant no insult and intended to complement Singapore for its influence greatly exceeding its island dimensions.