Healing in Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia seemed to be thread throughout this week. On Wednesday, the World Justice Project hosted a webinar to highlight Cambodia Bridges to Justice's work, as CBJ won the World Justice Challenge Prize last year. The prize is the result of a global competition to identify, recognize, and promote good practice and high-impact projects and policies that protect and advance the rule of law. In preparation of this event, the office was busy brainstorming speeches and compiling information on CBJ. I was able to assist in the preparations by taking notes on a conversation with a CBJ leader and suggesting ways to integrate the keynotes of the conversation into a speech.

The webinar was a great opportunity to learn about the present state of Cambodia's justice system and its harrowing history that it has risen from. CBJ began in 2005, when the country was still reeling from the Khmer Rouge, the communist regime that committed genocide and destroyed civil society. At the time CBJ began, Cambodia had no rule of law, as torture was the chief form of investigation and there was no means of securing individual rights. In fact, there were less than 10 attorneys in the entire country. Presently, CBJ has trained over 750 lawyers to fight for the rights of the most vulnerable. It operates in 20 out of 25 provinces and is the backbone of the country's legal aid system.

The World Justice Challenge Prize recognized CBJ's work in the Court of Appeals in particular. This is a focus of the program because appellate proceedings should be an opportunity to challenge unjust convictions. However, in Cambodia, people can remain in prison indefinitely waiting for their appeal case to be heard. The accolade awarded to CBJ is particularly significant because Cambodia was IBJ's first country program.

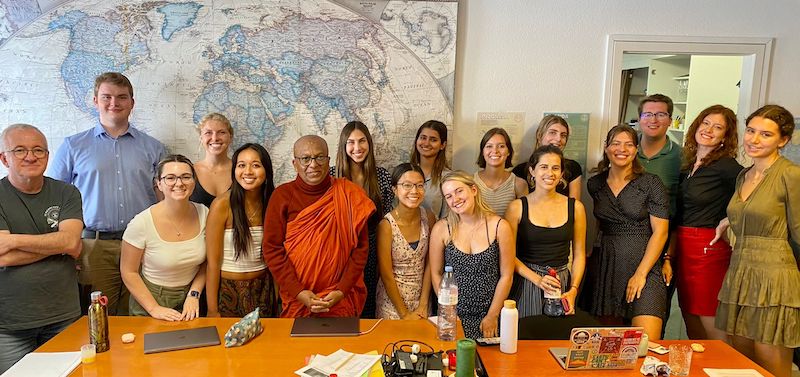

On Thursday, a Theravada Buddhist monk came in to speak with the interns. He is associated with IBJ through his commitment to social justice for marginalized communities in Sri Lanka, where IBJ also works. He currently heads an institute dedicated to training programs that support social healing, focusing on ameliorating interreligious and interethnic conflicts. Admittedly unfamiliar with Buddhism, interns were able to ask him questions about his faith journey, Buddhism's comparison to other religions, and what nonviolence means to Buddhism. I am grateful to have been present for this conversation, as Buddhism is the world religion I knew least about. I reflected on how prominent a role a region's major religion has in shaping the culture. For instance, whereas Judeo-Christianity's linear history has influenced the West's progress-oriented mentality, Buddhism's cyclical conception of life fosters a more introspective and communal culture in South East Asia. The monk's belief in the power of his religion as a means of social healing will certainly stick with me.