Week #5: Inshallah ("God Willing")

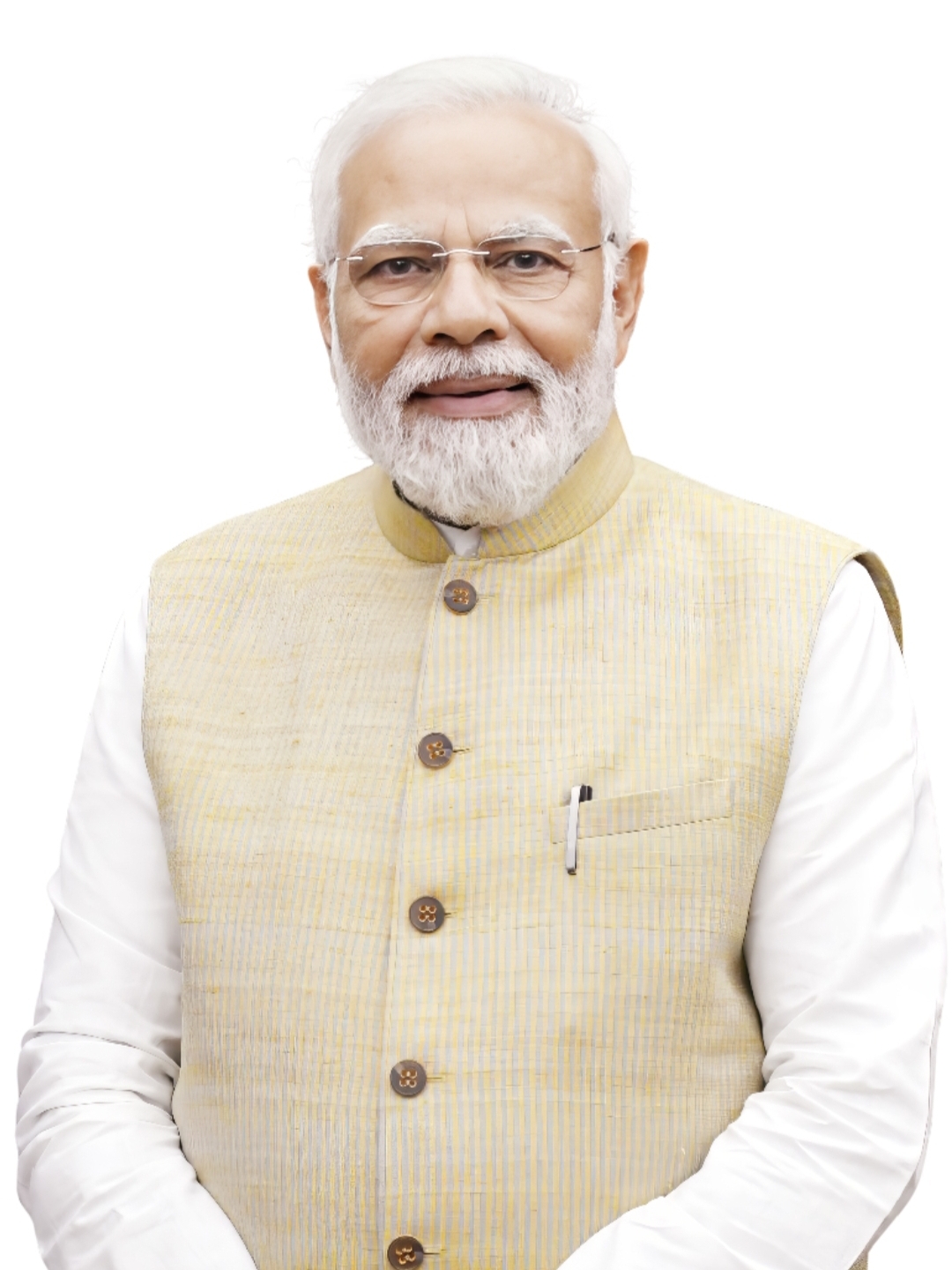

Upon arriving in India, one of the first stories that was told to me concerned a dispute over a sixteenth-century mosque. The mosque itself had been built in the northern Indian city of Ayodhya by a Muslim general linked to the mighty Mughal Empire, and its construction had been a longstanding point of controversy as a great many Hindus believed that it had been erected on top of the birthplace of the god Ram. This was an offense of such scope and severity that some found it difficult to overlook; in 1992, a group of Hindu militants destroyed the mosque, leading to the deaths of three thousand people (most of whom were members of India’s Muslim minority) in the riots that followed. Ten years later, a train carrying Hindu pilgrims who had traveled to Ayodhya caught fire, killing dozens in the Indian state of Gujarat. Muslims were blamed for the incident, and, with the tacit endorsement of Gujarat’s then-chief minister Narendra Modi, many Muslims lost their lives, businesses, or holy sites in the carnage that ensued. Twenty-eight years later, in 2020, now-Prime Minister Modi set a cornerstone for a new Hindu temple to be constructed on top of the site once occupied by the Mughal mosque in Ayodhya with the blessing of the Indian Supreme Court. This past January 2024, Modi returned to Ayodhya months ahead of the largest general election on Earth to inaugurate the temple even though its construction had yet to be completed; neither move was particularly shocking considering Modi and his political party, the BJP, have long had an enduring and considerable ire for Islam and its adherents.

to overlook; in 1992, a group of Hindu militants destroyed the mosque, leading to the deaths of three thousand people (most of whom were members of India’s Muslim minority) in the riots that followed. Ten years later, a train carrying Hindu pilgrims who had traveled to Ayodhya caught fire, killing dozens in the Indian state of Gujarat. Muslims were blamed for the incident, and, with the tacit endorsement of Gujarat’s then-chief minister Narendra Modi, many Muslims lost their lives, businesses, or holy sites in the carnage that ensued. Twenty-eight years later, in 2020, now-Prime Minister Modi set a cornerstone for a new Hindu temple to be constructed on top of the site once occupied by the Mughal mosque in Ayodhya with the blessing of the Indian Supreme Court. This past January 2024, Modi returned to Ayodhya months ahead of the largest general election on Earth to inaugurate the temple even though its construction had yet to be completed; neither move was particularly shocking considering Modi and his political party, the BJP, have long had an enduring and considerable ire for Islam and its adherents.

Somewhere close to MAP’s outreach office here in New Delhi (in a location that I have yet to pinpoint with any visual accuracy), there is another mosque. I know this for a fact because once during each afternoon and once more again in the late afternoon, a man’s piercing profession of faith can be heard coming from a distant loudspeaker singing in the formal Arabic of the Quran. Though I had certainly known what the singing was, I had never heard a call to prayer in person before. This was a facet of my personal experiences back in America that amused even many of my Hindu coworkers: “Surely there must be mosques in the United States of America?” they asked me. “I know for a fact that there are,” I respond, not defensively but more amused than anything else, “but believe it or not, they were none too prevalent in Pennsylvania Dutch country where I grew up. Now horse and buggies, on the other hand…” The call to prayer that I hear throughout the workweek is beautiful in a haunting sort of way, and I believe it is sung in a minor key; it doesn’t sound totally melodic to the Western ear, but its ability to captivate the listener is hard to deny (or at least, I certainly think so).

Ayodhya is not the only site where Muslims have faced persecution in India over the past several decades. Back in 2019, a significant piece of legislation spearheaded by the BJP was passed which established an easier pathway to  Indian citizenship for Pakistanis, Afghanis, and Bangladeshis coming into the country who could prove that they were practicing Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis, or Christians; missing from this list of course were Muslims (a hallmark and not a defect of the legislation). The so-called “Citizenship Amendment Act” was widely protested within the capital here in New Delhi, and many Muslims were either killed or arrested in the events that ensued. Several BJP politicians were later found to have actually helped incite the violence against Muslims in the city, and it was further uncovered that the Delhi police had done extraordinarily little to intervene against Hindu mobs that were set on attacking Muslims. “It was f**king terrifying,” my friend and fellow intern at MAP Saalima recounts to me one day. Saalima is a recent graduate of Jamia Millia Islamia, an all-Muslim collegiate institution in Delhi that was a focal point of the protests that occurred. “Thankfully, nothing happened to me, and no one that I knew died, but I had many friends who were arrested just for making their voices heard. I don’t know if there's ever really been a good time to be a Muslim in India, but things are scary for us now.” I later found out upon subsequent conversation with Saalima that many of her friends who were arrested back in 2019/2020 are STILL under arrest to this day.

Indian citizenship for Pakistanis, Afghanis, and Bangladeshis coming into the country who could prove that they were practicing Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis, or Christians; missing from this list of course were Muslims (a hallmark and not a defect of the legislation). The so-called “Citizenship Amendment Act” was widely protested within the capital here in New Delhi, and many Muslims were either killed or arrested in the events that ensued. Several BJP politicians were later found to have actually helped incite the violence against Muslims in the city, and it was further uncovered that the Delhi police had done extraordinarily little to intervene against Hindu mobs that were set on attacking Muslims. “It was f**king terrifying,” my friend and fellow intern at MAP Saalima recounts to me one day. Saalima is a recent graduate of Jamia Millia Islamia, an all-Muslim collegiate institution in Delhi that was a focal point of the protests that occurred. “Thankfully, nothing happened to me, and no one that I knew died, but I had many friends who were arrested just for making their voices heard. I don’t know if there's ever really been a good time to be a Muslim in India, but things are scary for us now.” I later found out upon subsequent conversation with Saalima that many of her friends who were arrested back in 2019/2020 are STILL under arrest to this day.

“What is your religion?” It's funny how many times I’ve been asked this question since coming to India; well, maybe it's not exactly funny per se, but the unrepentant directness in which the inquiry has so often been lobbed at me never ceases to bring a slight smile to my face. Me being me, I answer back diplomatically but truthfully: “I believe there is a reason why there is something rather than nothing. What that reason is, I don’t pretend to know or understand.” “Ok,” they inevitably respond, “but what religion are you?” Tired, my enthusiasm for the questioning increasingly waning, I then reply with an answer that appears to be more satisfactory. I have found it easier to go along and play this game of overt qualifiers and markers of one’s identity while I am here. I don’t know if my religious background is exactly favored in India, but it certainly does not appear to be disfavored from the reactions I get when I tell people that I was raised a Christian; for my own immediate well-being, I am grateful for that at the very least.

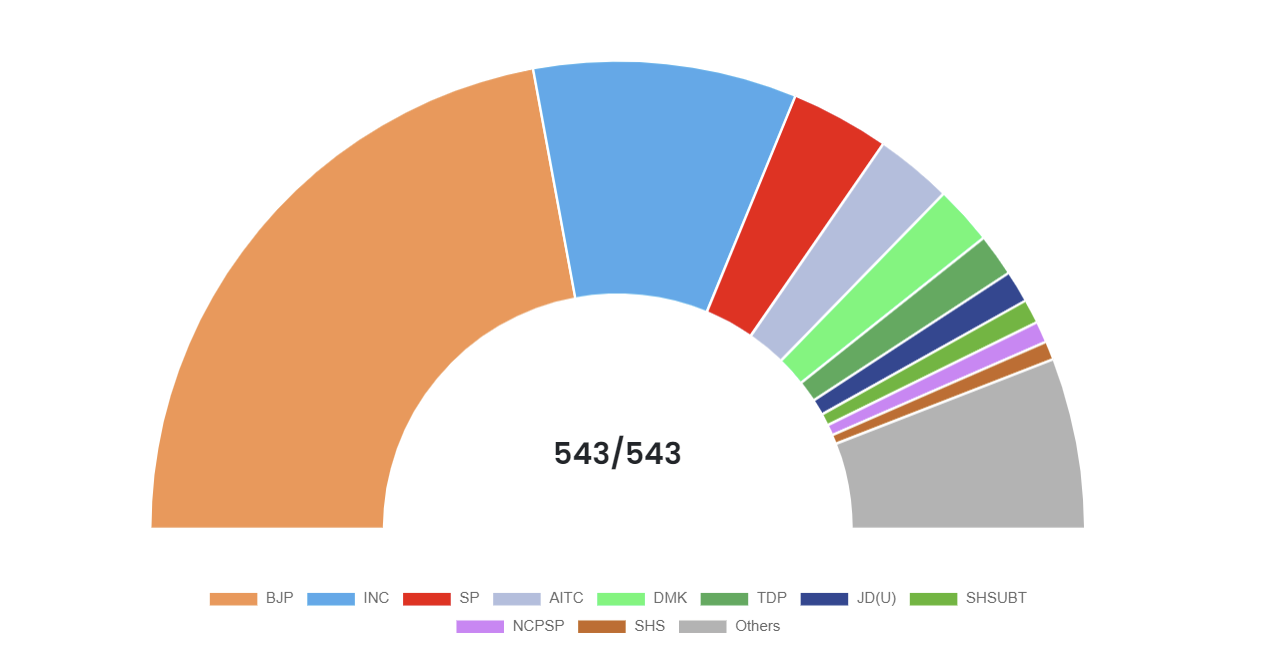

This was not the blog post that I had imagined writing even several weeks ago; this past June, India held its 2024 elections, and in the prelude to my formulating this post in my head, every poll available indicated that the Hindu-nationalist BJP party and its charismatic (if problematic) leader Prime Minister Narendra Modi would sweep the country in a landslide victory. The party retained control over the Indian government and Modi is still Prime Minister, but colleagues of mine at MAP have informed me that the party did not achieve the numbers necessary for them to carry a clear mandate to enact more of the anti-Muslim legislation that has been a hallmark of the BJP’s governance in the past. Instead, a coalition government has been formed, which will likely temper and humble Modi and his party's more overtly outspoken members. All of this appears to be good, probably even great, but it is worth reemphasizing the precarious position that 172 MILLION Muslims living in this country will still find themselves in in the months and years ahead. My friend Saalima feels comfortable enough moving around Delhi in her head scarf, a signifier of her religion and faith; she has told me that she knows many friends and colleagues of hers who do not feel similarly free and secure enough to follow suit.

Inshallah (literally translated to “if God wills it”) was a favorite phrase of mine that I heard often while studying Arabic as an undergraduate while pursuing my bachelor’s degree (I ended up minoring in it, which, having been taught Arabic during the age of COVID and classes held over Zoom, means that this signifier on my degree is all but ceremonial at this point rather than connoting any extensive ability or proficiency with the language). My primary professor, an endearing curmudgeon of a man we called Ustaadh (Professor) Gary, used to insert it into just about every oral language examination that I ever took with him: “What do you want to do after you graduate college, Tyler?” “After graduation, I hope to attend a good law school and get another degree, Professor.” “You hope to graduate college and then attend a good law school, Inshallah, Tyler. Inshallah, you will.” I don’t pretend to be able to comprehend the will or machinations of God, but I hope that conditions in India improve, both for my friend and for millions of other people like her. Inshallah, they will.

- Tyler Brooks, 06/29/2024