Week #2: Red Tape

My Indian odyssey began in earnest in February of 2024 when I was initially hired by the Migration & Asylum Project at the recommendation of Professor Warren. During my initial interview, two MAP attorneys whom I have come to know pretty well were very kind in making sure that I knew that if I needed any help obtaining the requisite visa materials necessary to conduct the internship, I should not hesitate to reach out to them for help. In hindsight, I think this kindness is a decision that they may have come to regret.

For those who don’t know, a visa is an endorsement put onto one’s passport that (ideally) allows the passport holder to enter, stay in, and leave a designated country indicated by the visa. Regardless of the ultimate destination in question, there are a myriad of different types of visas that a wayward traveler might be applying for - for example, there are tourist visas, student visas, business visas, and employment visas, just to name a few (all of which can be broken down further into fun little sub-categories of vague and largely unhelpful distinctions). The critical choice of which visa to apply for proved to be my first nearly insurmountable hurdle to coming to India. To understand why, I need to first describe the precise nature of my internship at MAP in some significant detail, as which visa a person applies for is inherently tied to their purpose in coming to a country. In conjunction with the powers that be at William & Mary Law School, I had been selected for employment at MAP for a duration not exceeding 10 weeks. Factoring in the four days that I had allocated to adjust myself to jetlag upon arrival in Delhi, this meant that I would be in India for exactly 72 days from May until August. While I am conducting work on behalf of MAP and have been contractually hired on as a “legal intern,” I am not a salaried employee. Any money I have received for the purposes of this internship I have received from the College of William and Mary, not MAP or any other entity located in India. In effect, this makes me an American intern volunteering on a short-term basis at an Indian non-governmental organization (or “NGO” for short).

The combination of these factors initially led me to believe that I should be applying for a student visa, which, as per the government of India’s “Visa Facts” webpage, contains a sub-category that is specifically designated for student “interns;” seeing as I was a student who would be arriving in India to conduct a so-called “internship,” this designation seemed particularly applicable to me. After making the mistake of beginning the student visa application, I reached out to MAP for confirmation only to be told by my employers that they “believed that I should be applying for an employment visa, but that [I] should double check this with the relevant authority in [my] country to be sure.” “OK,” I thought to myself; as far as I was aware, the only such “relevant authority” in my country was the Indian embassy in Washington, D.C., which I promptly attempted to call to have this seemingly simple question definitively answered. Upon calling the embassy, I was directed to a dial tone that unhelpfully told me to try again later, which I did several times throughout the afternoon and the next few days to no avail. Eventually, I was able to find a visa-specific Indian embassy email address to answer my question, but the person on the other end of this email address informed me that I had mistakenly contacted the Indian embassy (this I already knew). According to them, it was the Indian consulate tied to my permanent address that would best be able to tell me what kind of visa I needed to apply for.

While waiting for the Indian consulate in New York City to respond to my inquiry (at the time of this writing, I am still a permanent resident of Pennsylvania and not Virginia, where I currently live for the vast duration of the year, tying myself to the Indian consulate in NYC as opposed to the consulate office located in D.C., which in itself is a separate entity altogether from the Indian embassy that is also located in Washington D.C. Confused yet? So was I!), I reached out to knowledgeable persons at William and Mary who I thought might be able to shed some light on the subject. They collectively believed that the tourist visa would be most appropriate in my situation, as I was not technically employed at MAP so much as I was being hired as a sort of short-term legal volunteer. Eventually, the Indian consulate office responded and told me I should refer my question to the Indian embassy. After forwarding the consulate office the email that I had received from the Indian embassy explaining that I should, in fact, be directing my question to them, the Indian consulate office finally told me that I should apply for the employment visa over the student or tourist visas. Finally, I thought my visa problems had been solved once and for all.

Once I knew which visa application I needed to fill out, the actual application itself required an excess of information to complete but was otherwise fairly manageable. By early March, I thought that I had accumulated everything I needed to collect for the purposes of my application and, to be doubly sure, had specifically emailed the New York consulate with an itemized list of what I was planning to attach with my application, asking them to “[p]lease inform me if there is anything from this list that would be missing in order to file a proper visa application. Thank you!” Only twenty-four hours after submitting my visa materials in the mail, I received an alarming-looking email informing me that I had failed to send in the requisite materials for a proper visa application and that such materials needed to be sent back to the consulate’s office within fourteen days or else my application would be terminated. I was required to call the tolled number of my consulate to try and figure out what it was that I possibly could have forgotten to include. Apparently, in addition to the specified photograph attached to my application, I needed to have included an additional picture printed on glossy paper of specified dimensions for my application to be considered complete. Urgently, I rushed over to my local UPS store, had pictures taken of what at this point was a very panicked and sweaty-looking me, and proceeded to spend the next month and a half wringing my hands, waiting for confirmation from the consulate that my visa had been approved.

Such confirmation finally occurred in late April, after weeks of waiting and the date of my planned trip rapidly approaching; wanting to take advantage of all available accommodations, I had already purchased my airline tickets and made arrangements to stay at a Delhi-based Airbnb. By the time April rolled around, both of these were either partially or entirely non-refundable, making the reception of a proper visa all the more urgent. I was elated when I received the email that my visa application had been approved, but as I read on, I realized that there was a catch. Despite having previously mailed my passport over to the Indian consulate for the initial visa screening and having had my passport mailed back to me, it appeared as if I needed to send my passport to the Indian consulate again to be stamped for realsies this time (date of flight: t-minus three weeks). I proceeded to rush my passport over to the UPS store, paid the somewhat hefty price for expedited shipping, and was compelled to play the waiting game somehow yet again. Finally, FINALLY, my passport arrived back in the mail about a week and a half later, stamped with the requisite visa allowing me to travel to India. I thought that I could finally take a deep breath and that at least the procedural portion of my travel nightmares had reached their natural conclusion. This was not so.

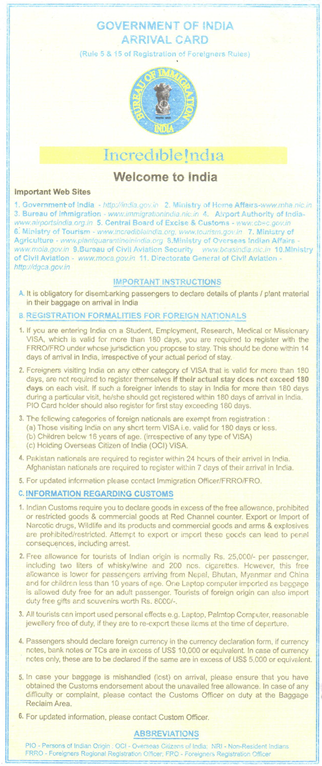

Upon disembarking from the eighteen-hour flight from D.C. to Delhi, I was handed a small piece of paper to present to the relevant immigration authorities in India. On the back of this paper, the following was written in tiny brown font: “If you are entering India on a Student, Employment, Research, Medical or Missionary VISA, which is valid for more than 180 days, you are required to register with the FRRO/FRO under whose jurisdiction you propose to stay. This should be done within 14 days of arrival in India, irrespective of your actual period of stay.” A series of curses spiraled around in my sleep-deprived head, followed by a pressing question: “What on Earth is the FRRO?”

Upon disembarking from the eighteen-hour flight from D.C. to Delhi, I was handed a small piece of paper to present to the relevant immigration authorities in India. On the back of this paper, the following was written in tiny brown font: “If you are entering India on a Student, Employment, Research, Medical or Missionary VISA, which is valid for more than 180 days, you are required to register with the FRRO/FRO under whose jurisdiction you propose to stay. This should be done within 14 days of arrival in India, irrespective of your actual period of stay.” A series of curses spiraled around in my sleep-deprived head, followed by a pressing question: “What on Earth is the FRRO?”

FRRO stands for the aptly if uncreatively named “Foreigners Registration Office.” As the name suggests, the FRRO is the branch of the Indian government tasked with “helping” foreigners with visa-related services upon their arrival in the country. Since coming to India, I have found that the mere mention of this agency tends to elicit one of three responses in those poor, unfortunate souls who have had the misfortune of grappling with the Indian bureaucracy: (1) a deep, pained eye roll, (2) a look of profound pity, (3) “Oh, not those ****ing people!” In my experience, all three are entirely valid and appropriate responses, though my own personal inclinations tend to favor the third. On paper, registering my arrival with the FRRO seemed simple, requiring the submission of thirteen documents to an online government portal upon which subsequent communications with the applicant could be made. Of these thirteen documents, ten I already had on hand as they had been provided to me by my employers for the previous visa application process. I was able to get two more documents from the “landlord” of the Airbnb that I was staying at. All that I needed to acquire for a successful submission with the FRRO was one final document: a proof of tenancy form to be signed by my landlord and stamped by the local police department, essentially showing that the person whose name was on the form was who they said they were and was staying in the specified address with the landlord’s knowledge and approval. Easy enough, right?

As I likely was going to be unable to properly communicate my needs to the local police department (most of the police in Delhi are fluent in Hindi rather than English), Nilam, an attorney with MAP, was kind enough to offer to take me there directly himself. Upon arrival at the MAP office one morning, I found out that I needed to have a printed photograph of myself to attach to the requisite form before it could be submitted to the police. Seeing as I am not quite vain enough to carry around printed color photographs of myself with me when I travel, I had to tell Nilam that I possessed no such picture and would need to procure one to properly submit the form. “No problem,” Nilam told me, “I know of a photo studio not far from here.” Approximately four hours later, I had acquired a series of small, colorized photographs capturing my exhausted likeness; the excessive time it took to acquire these pictures can be attributed to the fact that the photo studio that Nilam knew of, in addition to the following three photo studios that we attempted to visit, had all been permanently closed for reasons I couldn’t tell you. With a glue stick in hand, I quickly attached my likeness to the aforementioned form, and together, Nilam and I finally proceeded to the police office.

First, we ended up in an apartment complex that was crawling with cops – I am not quite sure how we managed to do this or why there were so many Delhi police officers in a single residential building, but we thought better than to ask any questions aside from “excuse me, sir, can you please direct us to the Greater Kailash police office?” After subsequently entering the police station, it took us about another ten minutes to locate the appropriate office tasked with handling residency forms, as every single person in the police station seemed to have a slightly different idea as to where this office was located in the building. Five minutes later, after handing the designated officer my filled-out form, the officer informed Nilam and I in Hindi that we had forgotten to include the requisite “C form,” the inclusion of which was not mentioned anywhere in the residency form that Nilam and I had downloaded directly from the Delhi police website. An hour and a half later, Nilam and I had (1) returned to the MAP office to fill out the form, (2) created a new, separate login with FRRO from the login I had been using to access FRRO services previously to even be able to access the C form, (3) had tried to fill out the C form three separate times only to have the FRRO webpage crash and fail to process the document, and (4) had finally printed out the C form and attached it with the residency document that we had attempted to have approved the first time.

Nilam and I then re-entered Delhi traffic to get back to the police station, only to later have the same officer that had “helped” us before now informing us that we were, in fact, at the wrong police station. You see, we had arrived at the local police station of Greater Kailash I when the location of my Airbnb was three minutes away from the station in the entirely separate area known as Greater Kailash II. Why didn’t the police officer inform us that we were in the wrong police station the first time we had shown up? This is an excellent question, but one to which I have no satisfactory answers. From there, Nilam and I proceeded to go to the correct police station, where an officer took one look at us before asking in Hindi, “So, where’s the landlord?” “What do you mean?” Nilam answered back, “The landlord has signed the form. See, it’s right here!” “No,” the officer responded back in a way that even to a non-Hindi speaker struck me as rather odd, “the landlord has to be physically present when the form is submitted to get my stamp of approval.” “The landlord isn’t currently in Delhi and won’t be for some time. Can I have our intern call the landlord so you can approve the form?” Nilam inquired. At this point, the officer smirked and left me alone in the office to talk to Nilam outside. When they returned, everything seemed to have been worked out, and the officer stamped the form in a manner that I found almost sarcastic (if the stamping of a government document can be described in such a way). At the time of this writing, all of my forms have been submitted with FRRO; however, I am still awaiting a response to find out if this saga will have yet another chapter added to it.

I am telling this story in its entirety not to complain – ok, I maybe wanted to complain a little bit, but that’s not the primary reason I am putting this experience into writing. My point in recounting this series of events is to highlight my own particular privilege; at every stage of my attempt to come to and stay in India, I had employers who were willing to help me do what needed to be done, support from my school and professors to help make my internship experience possible, and financial support from my family in the places where I required financial backing. The clients I have met since coming to MAP who are seeking refugee status do not typically possess these luxuries; often, they are persons who are still required to obtain some form of visa to be able to set foot in India but have the added baggage of fleeing some of the worst atrocities known to mankind: prolonged torture, horrific physical and sexual abuse, and complete and total economic destitution, just to name a few that have popped up in the last week of my working here. I would consider myself fairly well-off in life even absent this comparison, and despite this, I found the process of coming to India to be utterly daunting and overwhelming every step of the way. What must that process be like for those who have had everything stripped and taken away from them? Who have been compelled to navigate a system that is designed to keep them out on their own, devoid of resources or helplines? Who know that their journey doesn’t end when they acquire a visa and that even if they can make it to India, they will face the prospect of having to prove their own life story to the Indian government or UNHCR (the branch of the UN which conducts screenings to determine if a person qualifies as a refugee)? Right now, I am having a hard time imagining it, but my imagination will have to get a whole lot bigger a whole lot quicker if I am to provide clients with the help that they need in the weeks and months to come.

-Tyler Brooks, June 08, 2024