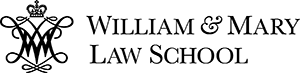

A Conversation with Professor Thomas J. McSweeney on His New Book about the Early History of the Common Law

by David F. Morrill

Thomas J. McSweeney joined the William & Mary faculty in 2013. His research focuses on the first century and a half of the common law. His published articles explore the legal-literary culture that flourished throughout Europe in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. He is particularly interested in the production of legal treatises in thirteenth-century England and what those treatises can tell us about the professionalization of the judges and lawyers of the early common law. His first book, Priests of the Law: Roman Law and the Making of the Common Law’s First Professionals, was published by Oxford University Press in November 2019 and released in the United States in January 2020.

Read more here.

The Bracton treatise plays a big role in this book. Can you describe Bracton for people who aren’t familiar with it?

Bracton is a legal treatise written over a period of about 30 or 40 years, between the 1220s and the 1250s, by a succession of justices working in the English royal courts. Justices seem to have kept handing it off to their clerks. Martin of Pattishall, who was one of the most important justices working in the generation after Magna Carta, may have been the first justice to work on the treatise. He then handed it off to his clerk, William of Raleigh, who was a really significant justice in the 1230s. He seems to have handed it off to his clerk, Henry of Bratton, who added some material and edited the treatise. The treatise takes its name from Bratton, whose name was sometimes spelled “Bracton” in Latin texts. C’s and t’s were easy to mix up in the kind of script they used. Bracton is interesting in that it’s written in the form of a Roman-law summa of the kind that were coming out of the universities throughout Europe in the thirteenth century, and uses Roman-law terminology and doctrines to describe the early common law. It’s considered part of the “canon” of early common-law texts. Our first law professor, George Wythe, owned a copy. Thomas Jefferson wrote about Bracton. It’s cited in the classic first-year property case Pierson v. Post, about who owns a fox. It’s one of those texts that many lawyers have heard of at some point, although few people still read it.

What got you interested in this topic?

I read some of Bracton in my legal history course in law school and read more of it in grad school. When I started reading historians on Bracton, I saw a lot of discussion about when it was written, who wrote it, and whether it accurately represents practice in the common-law courts of the thirteenth century. These are important questions, but I didn’t see much writing on what I thought was the really big question: why did anyone think it was a good idea to sit down and write this book? Bracton fills about 1,200 pages in its printed edition, and one of its authors claims that he worked “long into the night watches” writing it. So I started thinking about Bracton as a cultural artifact and trying to figure out what role it was intended to play in the culture of the thirteenth-century courts. Why did a group of busy justices and clerks of the royal courts think it was important to produce this massive Latin treatise?

What was your conclusion?

For the group of judges who wrote Bracton, the practice of writing a treatise was as important as the end product. I think we tend to assume that the purpose of a treatise is pretty obvious: it’s to teach people what the law is. That was certainly one purpose of Bracton, but in the book I argue that the practice of writing this treatise, and some other texts produced by the same circle of justices, was actually a way of making the claim that these justices were jurists of the universal culture of Roman and canon law. They had been trained in Roman and canon law, and had learned through their study that jurists were characterized by the types of texts they produced. They set out to produce those types of texts.

When did you say to yourself, “I need to write a book on this” and how far did you have to go to do it?

The book grew out of my doctoral dissertation. When I came back to it to turn it into a book, I realized that I wanted the book to be less about Bracton and more about the people who wrote it. Bracton has been edited, so for most of the early work on this project I didn’t have to travel far. I have a copy of the edition and translation that has my notes scrawled all over the margins (and glossing the text like that is a very medieval thing to do!). I did visit several archives and manuscript collections. I had to go look at some rolls of cases decided by Henry of Bratton in the 1250s. They’re still considered public records and they’re kept in the British National Archives. I examined several manuscript copies of Bracton and a collection of cases in the British Library that’s been dubbed Bracton’s Note Book. That one has marginal annotations that were probably made by Bratton himself. It’s always cool to think you’re holding a book that was held by a royal justice nearly 800 years ago.

What were some of the biggest challenges during this project?

The script of the period can be difficult to read. This is more of a problem with my current project, where I’m working with lots of manuscript sources. The Latin they used was heavily abbreviated and written in a tricky cursive script. It’s not like reading Latin in a printed text. You often have to figure out what the word is before you translate it. Sometimes it’s only in the process of translating the word that I realize that what I transcribed can’t possibly be right, and then I have to go back to the Latin and figure out what the word actually is. I remember one instance where I stared at a word that only contained about five or six letters and a whole bunch of abbreviations for several minutes before figuring out it was transgressionem [trespass].

What new and interesting questions came up in your research?

Although Bracton was written between the 1220s and the 1250s, it seems to have been most popular in the period between about 1280 and 1310. About 50 manuscripts survive—a large number of survivals for a medieval text, particularly one that wouldn’t have generated much interest outside of England—and virtually all of them can be dated to this period. But Bracton was terribly out of date by that time. There was a flurry of legislative activity between the 1260s and the 1290s that made significant modifications to the common law. A lot of what was contained in Bracton would still have been useful in the last decades of the thirteenth century, but a reader would have to be really careful with it, since so many rules had changed. And yet many of the manuscripts show evidence of use, like marginal annotations. Why were people so interested in this text, which was difficult to use and as likely to mislead as to illumine? That’s a question that I’m turning to in my next research project.

Why is Bracton still relevant today?

There’s the easy answer: Bracton still gets cited by the Supreme Court about once per term. It still has some cultural cachet. It can be used to give an extra little bit of legitimacy to a legal argument. People often cite to Bracton to say, “This principle has been part of the common law from the beginning.” When Bracton is cited, someone usually e-mails me to let me know. I often get a chuckle out of it, because, more often than not, the person citing Bracton is misinterpreting it.

There are lessons we can learn from Bracton, however. One is that common lawyers have not always been so inimical to civil law. We usually think of the common law and the civil law as two distinct legal systems, and there’s a tenacious narrative that presents the common law as a uniquely English, wholly insular, institution. There’s often a heavy dose of superiority in this narrative, as well. But the justices who wrote Bracton were working hard to demonstrate that they were part of the broader legal culture of Latin Christendom (as they would have perceived it), a legal culture with Roman and canon law at its core. They weren’t trying to do something different from what was happening in the rest of Europe.

I gave a talk based on the book project in London a couple of years ago. After the talk, a lawyer in the audience said “it’s so political.” Although I knew immediately what she was talking about (Brexit), I hadn’t quite anticipated that reaction to the project. One of the arguments proponents of the UK’s departure from the EU have made is that England’s common-law system is so distinct from the civil-law systems they have in most EU countries that they’re not really compatible. Sometimes there’s a historical element to these arguments, that England’s common-law system has always been distinct from the civil law. Priests of the Law at least suggests that some influential justices of the common law’s early decades didn’t think this way. But I’m not sure it provides a firm answer one way or the other. In the book I argue that these justices wanted to show that common law was just one constituent part of a broader civil-law culture, but I also argue that the justices had to work pretty hard to do this. By the 1220s there were already a lot of differences between the rules, doctrines and categories of common and civil law. The authors of Bracton sometimes go to absurd lengths to try to reconcile them, suggesting that common law and civil law were already quite distinct in a number of respects. But the book does demonstrate that these important justices, some of the people who helped to develop the common law right at the beginning, didn’t think they were creating something particularly English or that the law they were creating was superior to civil law. In fact, their view was quite the opposite: any law worth its salt should be consistent with Roman civil law.

How did codified texts spread throughout England before Gutenberg?

People copied statutes and treatises by hand! And they didn’t necessarily treat the texts of treatises with the same kind of reverence we would accord the text of a book today. They would update treatises if they discovered things that were out of date. Some copies of Bracton are updated to take account of statutes that were enacted in the late thirteenth century. Sometimes people would cut things that weren’t relevant to their own situation. If there was a topic the patron of a manuscript just didn’t care much about, he might not have that part of the treatise copied. And sometimes people would compare their copy with another copy and add things if the other copy contained more material. We actually think that Bracton as we know it today was a product of this kind of copying. Someone found a copy of the treatise as edited by Henry of Bratton, the last of the justices to work on it, but then found an earlier draft of the treatise. Bratton had cut a lot of material from that earlier draft, but the scribe noticed that this earlier draft seemed more “complete,” so he added all of that stuff Bratton had cut back in, sometimes in the wrong place!

Was there ever any resistance from people who weren’t trained in Roman law?

There’s an interesting aspect of the Bracton project that I wasn’t able to explore fully in the book, but that I plan to turn to in a future article: the Bracton authors’ view of the common law as a legal system that required lots of specialist knowledge to access. Bracton is written in a high Latin register that a lot of the people who worked with the common law—people like sheriffs, coroners, estate stewards, eyre jurors and even a lot of practicing lawyers—probably would have been unable to read. It assumes knowledge of Roman and canon law that most people would not have had.

That sounds like a very elite view of what it means to be a legal professional.

I argue in the book that Bracton was written with a very small audience in mind, and I think its authors had a pretty exclusive view of who should be staffing the judiciary. I also think that they had a pretty exclusive view of who “counted.” There was a burgeoning profession of lawyers in the middle decades of the thirteenth century, but you wouldn’t know it from Bracton. The treatise doesn’t mention them. It does mention, and directly address, justices and clerks of the royal courts. I think part of the story of the later thirteenth century is a story of justices and clerks starting to view lawyers as part of the club.

How did your background prepare you for a complicated project like this?

I was lucky in that I went to one of those rare public high schools that offers Latin, so I took four years of that in high school with a great teacher, Mrs. Sadlon. And I had some excellent history professors as an undergraduate at William & Mary. Phil Daileader, in particular, encouraged me in my interest in medieval history. I also think people tend to underestimate the degree to which law school changes the way you think. There is something to the notion of “thinking like a lawyer.” There are two ways I can think of that law school influenced the way I wrote this book. First, law school really got me interested in the culture of lawyers and how we attach meaning to our work, one of the major themes of the book. Second, my property class with Greg Alexander, in particular, made me think about law as this artificial lens through which we see the world. As I tell my students, by the end of the property course, they’ll walk down Duke of Gloucester Street, and they’ll no longer notice the cobblestone streets and blooming flowers. They’ll see the world as it truly is, a complicated set of property interests: easements, covenants, estates and future interests. I often think that property law is the most obviously artificial of the fields of law that students study in the first year. We’ve overlaid the world with a set of abstract interests that exist only in the mind. This way of thinking about property really influenced chapter three, in which I discuss the very different ways in which Roman jurists and Anglo-Norman elites thought about the relationship between people and land, and the Bracton authors’ attempts to reconcile the two.

I also had a great adviser as a graduate student at Cornell, Paul Hyams, who encouraged me to think about the legal doctrine I found in Bracton in its cultural context. Thinking and writing about legal doctrine is a particular type of cultural practice. We can’t just assume that writing a treatise was a natural or obvious thing to do. We have to think about the reasons why people chose to do this rather than something else.

What can today’s students and law scholars learn from this type of history?

One of the themes of the book is the ways people attach meaning to their work. This group of judges working in the courts of the English king might have seen themselves primarily as administrators whose job was to look after the king’s interest. In fact, I suspect many of the royal justices of the early thirteenth century did think about their work that way; a good number of them started out as estate stewards, and some even left the judicial bench to go back to being estate stewards. The justices who wrote Bracton imbued their work with an entirely different kind of meaning. They used different metaphors for thinking about their work. They weren’t the king’s stewards; they were the law’s priests. They imagined themselves as jurists of the universal law of Christendom, giving their work an almost transcendent aspect. We, as lawyers, still imbue our labor with quite a bit of meaning. A friend once said that he thought the only organization that is better than a law school at convincing you that you had been turned into something new and different than you were before is the Marine Corps. I think we can use the Middle Ages as a kind of mirror for our own time. How should we, as lawyers, think about our work? What kind of meaning should we attach to it?

What’s next for your research?

From August to December I was a visiting fellow at Clare Hall, one of the colleges of the University of Cambridge. This was a wonderful opportunity. Cambridge has a Centre for English Legal History and some of the world’s top experts in the history of English law. It also has an amazing collection of medieval manuscripts. I was living practically across the street from the Cambridge University Library, and spent a lot of time with texts that historians generally call statute books. These are manuscripts that are usually about the size of a modern hardcover novel. People started to create them in the second half of the thirteenth century, and they usually contain a full set of the statutes that had been enacted up to the point at which the book was written. They usually also contain a collection of short treatises on the common law. They were likely created as reference works or handbooks by lawyers, estate stewards and county elites. I’m really interested in the treatises. Treatise-writing exploded in the second half of the thirteenth century. There are dozens of short treatises, written in French and Latin, some of which have been edited, but many of which exist only in manuscript form. While I was in Cambridge I started working on one in particular, the Summa de Bastardia (Treatise on Bastardy). It’s a Latin text that includes a series of hypothetical cases about inheritance, most (but not all) of them about illegitimacy and its effects on inheritance. There are at least 93 manuscripts in existence, which is a huge number of survivals for a medieval text. It must have been wildly popular. But I’ve never seen more than a few sentences written on it. Texts like the Summa de Bastardia are really important, because they’re some of the earliest evidence we have for the education of lawyers in the common law. These are the kinds of texts people read to learn how to practice in the courts. Some of these treatises appear to have been based on lecture courses that we know little or nothing about. There’s a ton of material to work on, and I plan to build on the work of other scholars who have worked on some of these treatises to give us a fuller picture of legal education in the early common law.