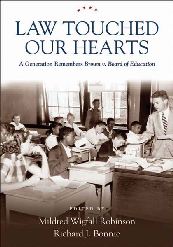

Professors Recall How Brown v. Board Shaped Their Lives in New Book, Law Touched Our Hearts

|

Five William & Mary faculty members are among forty law professors from around the nation who contributed essays to a new book entitled Law Touched Our Hearts: A Generation Remembers Brown v. Board of Education (Vanderbilt University Press 2009). Four of the professors - Linda Malone, Larry Palmer, Davison M. Douglas, and Paul Marcus - joined Mildred Wigfall Robinson, one of the book's co-editors, for a panel at the Law School on Feb. 26 to talk about their essays. The fifth contributor, Kathryn Urbonya, was not able to join the panelists that afternoon. The panel was sponsored by the Dean's Office, the Black Law Students Association, the Institute of Bill of Rights Law, and the Human Security Law Program. Robinson, the Doherty Charitable Foundation Professor at the University of Virginia School of Law, conceived of the book with co-editor Richard J. Bonnie, her colleague at the university and the Harrison Foundation Professor of Medicine and Law. "The book's premise is really quite simple," Robinson told the standing-room only audience, "that the law and Brown, and what it stood for, touched the hearts of children in a way that has been quite formative, not just for the people who wrote these essays, but for a whole generation of Americans." The title, she explained, came from a conversation between Chief Justice Earl Warren and President Eisenhower "during the time the Court was considering the case. Eisenhower was doubtful that an order from the Court ending school segregation would be successful. After all, as he put it, law cannot change the hearts of men." Professor Linda Malone said she grew up in Chattanooga, Tenn., where she was raised by parents whom she said "by any definition ... were racist." In talking about her essay, "Crossing Invisible Lines," she vividly described to the audience her memory of "riding the incline" up Lookout Mountain to elementary school every morning, alongside black men and women traveling to work. She recalled that the public bathrooms at the top of the mountain had "one set designated for 'white,' one designated for 'colored.'" By the end of her elementary school education in 1964, such racial designations were eliminated, but the effects of segregation were not so easily erased. Some of the passengers on the incline, she recalled, "had trouble walking into those bathrooms from which they had been previously prohibited. They had become so accustomed to that designation that they were uncomfortable crossing what I call those 'invisible' lines." Malone described having the courage to cross an invisible line in her own life, when she came to the realization as a young girl that racism was wrong, and began to distance herself from her parents' racist beliefs and those of many around her. Reading The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, she said, "was a revelation to me ... because that is basically what Huck Finn discovers." "I was Huck Finn. I had been raised in a very racist way. I couldn't understand why I started feeling differently, but I felt differently. I eventually realized from the people I met that it [racism] was just wrong. It was just, quite simply, wrong." Professor Larry Palmer grew up in St. Louis, and he spoke about the heroes that figure prominently in his essay, among them his elementary school teacher, Dr. Hyram. Hyram, he told the audience, had studied at the Sorbonne on a Fulbright and earned his doctorate, but racism limited his professional path to teaching at an elementary school. Palmer and 20 or so other children were assigned to him as gifted students. Among them, a lone white student, whose parents petitioned the school board to have their daughter assigned to the class. "And I think he [Hyram] decided that because there was so much controversy about Cynthia [the white student] being in our class, that we were going to be the top achievers." He added wryly, "no child left behind." Later, in city-wide testing, the results of Hyram's efforts became apparent to all: "the top ten students ... were in our class. Nine black and one white." Hyram encouraged Palmer to apply to the renowned Phillips Exeter Academy, convincing Palmer's reluctant parents to let him go when he was offered a scholarship. Palmer became one of only a handful of black students at the school at that time. His parents, also educators, had carefully shielded him in his early life from experiencing racism as much as they could. For example, they steered their family clear of segregated restaurants in their own neighborhood. "I give them a lot of credit for being able to protect, yet push forward at the same time," he said. "There was so much loving care in my story," Palmer said, "It's about people who thought about the future generation and just devoted so much care." Professor Davison Douglas told the audience that growing up in Charlotte, N.C., he lived in "a white world." "My church was white. My school was white. My Boy Scout troop was white ... almost my entire world was white until the fall of 1969." That year, Charlotte "would begin what would become the most extensive school desegregation program in the United States." He recalled that the public school he attended, once entirely white, became about 70 percent white and 30 percent black in his eighth-grade year. The change was an uneasy one at first, he recalled, with fights sometimes breaking out. During one, Douglas was cut with a razor blade. His parents, though upset by the incident, decided against enrolling him in a private school. "My parents were fundamentally committed to public education," he said, and then added with a nod to his younger self, "and I was fundamentally committed to staying with my friends." He recalled that white and black students often came together for extracurricular school activities. Long car rides to debate tournaments and nights spent in hotels when the team was on the road provided an opportunity for in-depth conversations with his black teammates about their lives and experiences. He said he titled his essay for the book "A Different Kind of Education" in gratitude for those conversations in which he learned how race had affected his teammates' lives. Those conversations profoundly enlarged Douglas's view of the world and provided a "wonderful education, an education I would not change ... I got to live in someone else's life." Professor Paul Marcus attended public schools in the Los Angeles Unified School District in the mid-1950s to early 1960s. Los Angeles at the time had de facto segregation, he said, due to districting based on housing patterns in which the "east side of town was almost entirely black, out to the west ... almost entirely white." He grew up in the city's center and attended a large, public high school that was atypically diverse, both racially and economically. It was economic disparities between students, rather than racial ones, he said, that often sparked the greatest conflict. It was puzzling, he noted, to graduate from a racially diverse public high school and find that in the same city there were few people of color teaching or studying at UCLA, where he received both his undergraduate and law degrees. In his essay, Marcus said that he looked at the demographics of the Los Angeles Unified School District in the period when he was a student and compared them to the demographics of the district today. While the racial composition of the general population in the district has changed some he told the audience, racial diversity in the district's public schools has suffered greatly in the past thirty years. There are now a tremendous number of private schools, Marcus said, "overwhelmingly white, private schools." In addition, he said, a large number of people moved from the district to cities west of Los Angeles, such as Santa Monica, cities "that traditionally had very good school districts and that were not subject to any order under the Los Angeles Unified School District litigation." His experience of attending a diverse public school "would not be duplicated today." Editor's Note: Professor Kathryn Urbonya was unable to attend the panel. In her essay, "Entering Another's Circle," she recalled her childhood in Beloit, Wis., and an ever -expanding circle of people -- including her mother, a high school counselor, and a college roommate -- whose wisdom and encouragement made a difference in her early life. She writes with poignant insight about the richness gained when we invite into the circle of our lives those whose race, religious beliefs, sexual preferences or economic backgrounds may be quite different from our own.

|