Interactive Forum Promotes Conversation about Free Speech on Public College and University Campuses

The College of William & Mary hosted an interactive forum about free speech on college and university campuses on January 25 at the Sadler Center. The program was co-sponsored by the Division of Student Affairs, the Office of Diversity & Inclusion, and the Student Assembly. William & Mary then concluded what has been a series focused on free speech with a day-long symposium entitled The First Amendment, Protest, and the Role of State Actors. The symposium was hosted at the Law School and co-sponsored by William & Mary and the American Civil Liberties Union of Virginia.

Law School Dean Davison M. Douglas facilitated the discussion at the Sadler Center by presenting a series of “speech scenarios” based on actual events that have occurred on campuses around the country. He said the issue of hate speech on campuses was among the most pressing issues facing higher education.

Dean Douglas invited audience members to consider how a public college or university would appropriately respond under current law in each scenario, and to cast their votes on outcomes for each scenario using their cell phones, tablets or laptops. Online polling software quickly tallied and displayed the results. Professors Vivian Hamilton and Timothy Zick of the Law School faculty and Dean of Students Marjorie Thomas were on hand to share their perspectives.

Douglas posed a question at the start of the event to test the audience’s knowledge of an important legal principle: that the First Amendment explicitly imposes on only government actors, such as public colleges and universities, the obligation to protect speech.

As part of the discussion that followed, Douglas invited Zick to give a brief overview of the First Amendment’s free speech clause. Zick is the author of three books: “Speech Out of Doors: Preserving First Amendment Liberties in Public Places” (Cambridge University Press, 2009); “The Cosmopolitan First Amendment: Protecting Transborder Expressive and Religious Liberties” (Cambridge University Press, 2014); and “The Dynamic Free Speech Clause: Freedom of Speech and Its Relation to Other Constitutional Rights” (forthcoming, Oxford University Press).

“The free speech clause of the First Amendment protects a broad range of communications, with just a few categorical exceptions,” Zick told the audience. Those exceptions include, for example, speech that incites violence, threats, libel, child pornography, and obscenity. The justifications for such broad protection, he said, have developed over time and have endured despite periods in our history in which speech rights were not afforded equally to all citizens. Those justifications are that free speech facilitates “free inquiry and the search for truth,” promotes self-government by “an enlightened and intelligent citizenry,” and provides a bulwark against authoritarianism, government censorship, and abuse of power.

“Today’s protection for countercultural ideas or countercultural identities is the product of a revolution that took place in the twentieth century with regard to free speech doctrine,” he said. “That revolution extended protection to speakers whose speech was at one time considered dangerous or harmful, including atheists and religious skeptics, religious speakers, civil rights protesters, anti-war protesters, advocates for same-sex marriage, and advocates for abortion rights.”

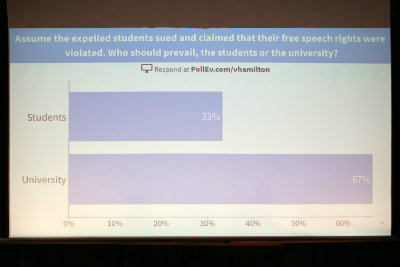

In one scenario discussed, two students were expelled from a public university after they were videotaped leading a racist chant on a bus that was taking members of a fraternity to an event. The  question posed to the audience was: “Assume the expelled students sued and claimed their free speech rights were violated. Who should prevail, the students or the university?” Although almost seventy percent of the audience said the university should prevail, the panelists said the students would likely prevail in court on free speech grounds, despite the deeply offensive content of their speech.

question posed to the audience was: “Assume the expelled students sued and claimed their free speech rights were violated. Who should prevail, the students or the university?” Although almost seventy percent of the audience said the university should prevail, the panelists said the students would likely prevail in court on free speech grounds, despite the deeply offensive content of their speech.

Hamilton, who teaches courses in Education Law and Race and the Law, said that any discussion of the legal protection afforded to speech would be incomplete without acknowledging the corrosive effect of hate speech on society and on the dignity of the individuals it targets. In addition to her appointment as a Professor of Law, Hamilton is an affiliated professor with the Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies program.

“Hate speech communicates to members of the targeted group that they are not welcome and equal members of society,” she said. It “draws on and intensifies the effects of stigmatization that members of the targeted group have previously undergone.”

Additional scenarios focusing on free speech guarantees on public campuses included admitted applicants exchanging racist and anti-Semitic communications on Facebook and students “chalking” provocative and anti-Muslim statements on university sidewalks. Panelists and the audience also discussed cases in which schools grappled with the cost of providing security for a white supremacist speaker, as well as students who shouted down or physically accosted a controversial author.

The Division of Student Affairs at William & Mary seeks to engage students in an ongoing conversation about how to talk about difficult issues as a community, Thomas said. As Dean of Students, she takes seriously any concern voiced by a student or group of students about speech that makes them feel unsafe or unwelcome on campus. She noted that professional organizations such as Student Affairs Administrators in Higher Education and the Association of Student Conduct Officers are engaged in discussions about how administrators can protect free speech rights on campus while also ensuring the safety of students and maintaining a learning environment conducive to their institutions’ mission.

About William & Mary Law School

Thomas Jefferson founded William & Mary Law School in 1779 to train leaders for the new nation. Now in its third century, America's oldest law school continues its historic mission of educating citizen lawyers who are prepared both to lead and to serve.