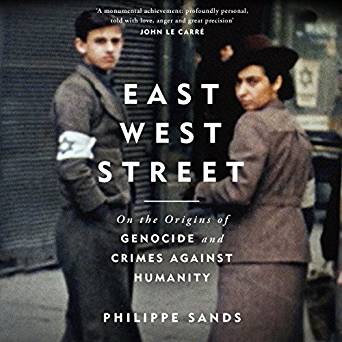

On the Origins of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity

I finished reading a book that lined up perfectly with my work (and travels) over the summer. It might be one of my favorite books I have ever read, and it made my trip to Auschwitz and Krakow even more personal and poignant. The book is titled East West Street, written by Philippe Sands, a professor of law at University College of London. It weaves together both Sands's own family history through WWII and the history of the terms "genocide" and "crimes against humanity." To do this, he examined the lives of Raphael Lemkin and Hersch Lauterpacht, the lawyers who coined the terms "genocide" and "crimes against humanity," respectively. Lemkin and Lauterpacht have an almost eerie connection to his own family in Poland, with Sands's grandfather having lived on the same street as Lemkin at one point in time. What makes this book so interesting to me is the personal nature of it all. Both Lemkin and Lauterpacht were Jewish and were personally affected by WWII, having fled from persecution, often with family members ending up in concentration camps throughout Europe (some in the same camps as Sands's family members).

This book examined how two terms, never having been used before in a prosecution, both have good intentions, but may not mix well after all. Through their experiences, Lemkin focused on the destruction (and necessary protection) of groups. Lauterpacht, on the other hand, focused on the individuals and the specific crimes targeted to each individual. Oddly enough, even though both Lemkin and Lauterpacht both wanted to use their own term to prosecute Nazis at the Nuremberg trial, there was a clash between both ideas. Sands notes that Lemkin and Lauterpacht likely were in the same room as each other at one point, but they never sat down to discuss their ideas. Through talking to family members, however, it became clear that each legal scholar did not approve of the other's term. Lemkin thought it was necessary (above all else) to protect groups as a whole, where Lauterpacht thought that doing so would "reinforce latent instincts of tribalism, perhaps enhancing the sense of 'us' and 'them', pitting one group against another" (quotation from East West Street, p. 117). These are points of contention in which I had never before considered. I have to think that Lauterpacht had a point, although it is useful to have the Genocide Convention and therefore a definition to use in prosecution. This book, coupled with my work this summer, helped me understand why it is so difficult to prove genocide, and the implications of prosecuting genocide. Genocide is seen as the crime of all crimes, and in now understanding how difficult it is to prove, I understand why. Despite the disagreement Lemkin and Lauterpacht had in their writings and proposals, I find it necessary (and possible) to have both definitions working in tandem. After seeing what happened in Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia, the crime of all crimes seems to be appropriate - regardless of how difficult it is to prove. However, crimes against humanity seems equally important for dealing with specific events carried out towards individuals.

All in all, this book was fascinating, and I felt it necessary to capture my thoughts on it. The work I am doing this summer will stick with me for years to come - not only from gaining this experience, but from the implications of issues just like I described above. Each day I come into work, there are always intellectual discussions about these issues and the implications they will continue to have in decades to come. I am so thankful for this opportunity, and I cannot believe that my time here is dwindling down so quickly.