Week 3: Visit to Court; the Killing Fields

This week, a new intern from Germany joined me at the Phnom Penh office. On his first day, we discussed some shared goals for the summer, which included attending court in Cambodia. We were thrilled when our co-worker invited us to join him at the Appeals Court on Friday.

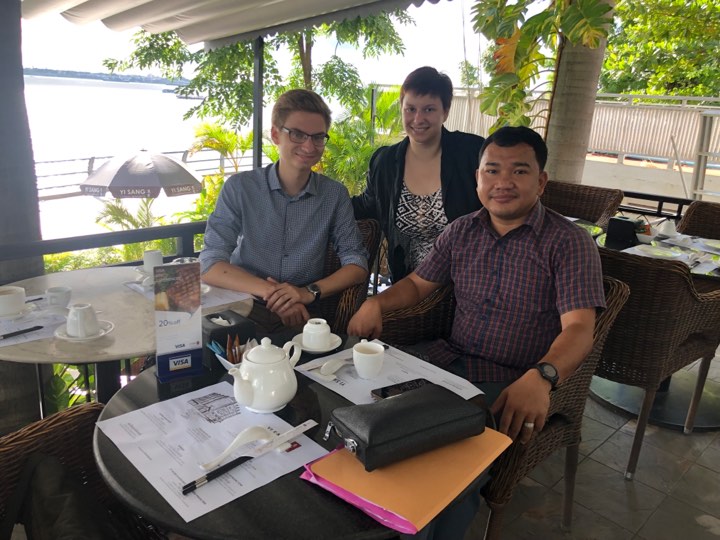

Simon, me, and Appeals Court lawyer Sophoes Phon before court

Sophoes Phon, the IBJ lawyer who I mentioned in my first blog post, was scheduled to argue two criminal appeals at the court that day. He represents both clients free of charge, as part of IBJ’s mission to provide access to justice. Simon (the other intern) and I met him before court to learn about the cases. One client, he told us, had been convicted of drug trafficking, while the other had been convicted of rape. In both cases, he would appeal the client’s sentence, set at the median point between the minimum and maximum penalty. I asked if this was usual, and he explained that judges do take aggravating and extenuating circumstances into account, so the sentences vary. In regard to the drug-related case, at least, he was hopeful.

Overall, I was surprised that the court proceedings were not radically different here than in the U.S. I have never observed court in a civil law country before, so I imagined a more divergent experience. A few striking differences, however, included the following:

- The court heard six criminal appeals in one session

- Each of the defendants sat in the courtroom along with the other defendants until his case came up

- A juvenile offender’s case was among those heard during the session

- Three judges attended the proceedings, and occasionally one would leave the room as the session continued

Today, we heard the verdict of the appeals. While the judge did not reduce the ten-year sentence of the client who committed rape, he reduced the sentence of the client found with drugs from two years to six months.

More Experiences in Cambodia

On the weekend, I met a Cambodian friend who I got to know in 2010-2011, when she studied at my undergraduate university, Bard College, through the Harpswell Foundation. She has now worked as a paralegal in Phnom Penh for six years, at a firm that primarily represents international developers. I was interested to hear her unique perspective on property rights issues, especially in relation to title, which I'd been told was complicated here.

She explained that many farmers living in the provinces outside of Phnom Penh do not have title to their land, though they may have been living on a given parcel of land for decades. Others have “soft title,” recognized only at the local level. “Hard title” requires an official survey of the land’s boundaries, and remission of a four-percent tax on the value of the land. When a property has both hard and soft title, the hard title wins. Therefore, for example, if the government grants land to a developer, the developer’s hard title supersedes any local farmer’s soft title. While this has occurred in the past, my friend told me that international pressure has led the government to become more careful about carving out areas for those who live and work on the land when they make grants to developers. The government has also worked to issue hard title to those in actual possession of land in the provinces.

We didn’t spend our entire time together talking about law, however. After a delicious lunch at the hip vegetarian restaurant Backyard Café, my friend told me that she had made her whole afternoon free, and we could do whatever I wanted around the city. I was at a loss for what to suggest. But, since we had her car at our disposal, she suggested we might do something a bit out of town: how about visiting Choeung Ek? Her suggestion surprised me. Commonly known as the Killing Fields, almost 9,000 people died at Choeung Ek during the Khmer Rouge regime. Wouldn't it be too sad for her? No, she said. She had already been there many times, and found it an important and moving site to visit. She would be happy to take me.

I learned there that the mass graves of those killed at Choeung Ek had been exhumed in 1980, during the Vietnamese occupation of Cambodia. What was left were large, evocative hollows in the earth. Clothes and bones continue to surface here after every rain.

My friend stayed with me as I listened to an audio tour that narrated the devastating routine of genocide conducted where we stood. A lake marks the eastern-most border of the property, and path leads around it, offering a needed break for reflection. When I paused the audio tour, I asked my friend about her own family. Her parents were already married when the Khmer Rouge came into power, but were separated, and made to live in single-gender communities, throughout the regime. At one point, my friend’s father was sure his wife had died. The only reason they both survived, she said, was that they had grown up as farmers. Not only did they avoid the suspicion automatically conferred on urban dwellers, but they also knew how to grow rice, and therefore would not starve.

The skulls exhumed in 1980 have been housed in a central stupa that is seventeen stories tall. This monument must serve a dual purpose. Most importantly, the monument honors the memory of those who died during the Khmer Rouge. But also, the monument cannot but act as a reminder that we—lawyers, global citizens—have a duty to demand justice for people facing terror and suffering at the hands of an oppressive regime.