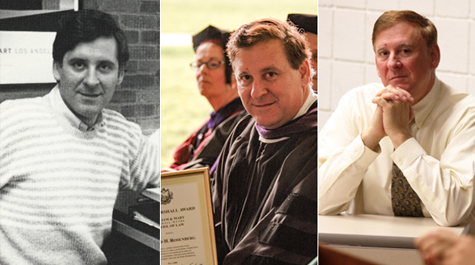

Professor Ronald Rosenberg Retires After Nearly 40 Years at William & Mary Law School

During a career as a lawyer and nearly 40 years as a law professor and administrator at William & Mary, Ronald Rosenberg has been known as a builder—of lawyers, of legislation, of academic programs, and of communities and relationships.

That’s not surprising when you learn of his early interests.

“As an undergraduate, I was interested in studying architecture at Columbia, and thought I was going to be an architect,” says Rosenberg, who retired as Chancellor Professor of Law Emeritus this semester. “But I hit my limits in terms of my ability to design buildings and decided it was not the work for me.”

The urge to plan, design and build, however, continued when he majored in political science with a minor in economics at Columbia, and then went on to UNC Law School where he was awarded a Mellon fellowship in law and city and regional planning.

As Rosenberg notes, “it was still a case of applying architectural ideas to my work, but building community over physical space.”

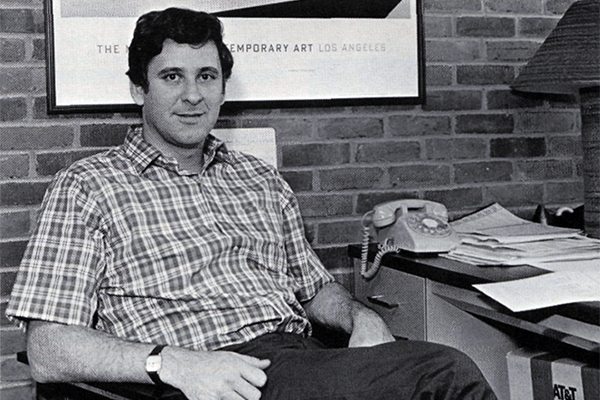

A native of Montgomery County, Maryland, Rosenberg had opportunities to work for private firms in nearby Washington, D.C., or New York City, but the combination of law degree with a technical four-and-a-half year program steered him toward something more policy oriented.

And so he took a job in the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Washington, D.C., headquarters, working directly for the Administrator in the Office of Legislative Counsel.

“In the 1970s, the most important federal environmental acts were being passed; it was the genesis of major environmental law,” Rosenberg says. “I worked there three years—an unbelievable experience for someone right out of law school.”

Fully 50 percent of Rosenberg’s time was spent on Capitol Hill, working with Congressional House and Senate staffs on the Clean Water Act, amendments and other significant environmental and conservation laws.

“It was a really heady time, and the work representing the agency’s interest was extremely educational and demanding,” Rosenberg says.

It was only when his colleagues started leaving for jobs in firms and Congress that Rosenberg began to consider taking another path in his career. Once again, he could have gone into big law, but his father, a federal administrative law judge, nurtured the idea of turning to academia.

Rosenberg joined the faculty at Cleveland State School of Law and spent three years—not surprisingly—teaching environmental law.

“Environmental Law was a new topic in the 1970s with a lot of student interest,” Rosenberg says.

Rosenberg soon built on that interest with his own scholarship and one of the most frequently used environmental law textbooks. In 1985, Professor Thomas J. Schoenbaum, then the Dean Rusk Chair of International and Comparative Law and Executive Director of the Dean Rusk Center for International and Comparative Law at the University of Georgia, asked him to co-author Environmental Law Problems, Cases, Readings and Text, one of the first environmental textbooks. Published as part of the University Casebook Series at Foundation Press, the work was considered seminal in its field for almost two decades, and has been revised and updated in many editions over the years.

Rosenberg wasn’t looking to leave Ohio, but one day he received a phone call from William B. Spong Jr., Dean of the William & Mary Law School (1976-85) and former U.S. Senator from Virginia.

Was Rosenberg interested in William & Mary?

Rosenberg admitted he hadn’t considered it, but took a trip to Williamsburg in the spring of 1982. He discovered a (then) tiny community and a brand new law building for the oldest Law School in the nation.

A welcoming faculty, including Professors Lynda Butler and Fredric Lederer (the former who is also retiring this year), sealed the deal, and Rosenberg began his long tenure in August of 1982. Since then, generations of students have benefitted from his teaching of property law, environmental law, local government, land use and related subjects.

A welcoming faculty, including Professors Lynda Butler and Fredric Lederer (the former who is also retiring this year), sealed the deal, and Rosenberg began his long tenure in August of 1982. Since then, generations of students have benefitted from his teaching of property law, environmental law, local government, land use and related subjects.

Professional service played a large role in the early part of Rosenberg’s academic career, the first stage of which he refers to as “conventional.” He served, for instance, the Association of American Law Schools (AALS) as chair of its Property section and Environmental Law section, and several other organizations.

After a point, Rosenberg decided to become involved in public policy development in Virginia. Because of his background in city and regional planning and environmental law, he was appointed to a new state agency—the Chesapeake Bay Local Assistance Board—by then Governor Gerald Baliles. The board’s purpose was of great importance—writing a set of rules for development of land in agriculture in the Chesapeake Bay region.

“This was very important state policy we were setting, and it was a real eye opener for me,” Rosenberg says. “It put me in touch with real public policy areas, and although it was highly political, I found it very interesting and had a great experience out of it drafting the state’s Chesapeake Bay development rules.”

A few years later, Rosenberg was appointed by then Governor Bob McDonnell to the Virginia Offshore Wind Development Authority, which encouraged the development of wind power. Although he found this job more frustrating and less consequential than the local assistance board, Rosenberg says it confirmed his long-held beliefs in the efficacy of wind power and in preserving the Chesapeake Bay region.

“In both instances my intuition was borne out over time,” Rosenberg says. “Wind power and the quality of the Bay were good issues to get involved with.”

Rosenberg’s efforts took an international turn in the 1990s when then Law Dean Taylor Reveley saw potential growth in the Law School’s small international program and asked Rosenberg to increase its size and to promote the Law School abroad. Anticipating an increase in foreign students interested in pursuing American law, Rosenberg went to work.

As director of the School’s Master of Laws (LL.M.) program for foreign lawyers, he planned not only to bring in more students to experience a William & Mary legal education, but also to heavily promote the Law School in other parts of the world.

“It was as important to me to establish relationships with foreign universities and law schools as it was to bring students here to learn American law,” Rosenberg says. “We needed to h ave credibility as to who we were and where we were as a law school.”

ave credibility as to who we were and where we were as a law school.”

Rosenberg began to develop institutional connections with faculty and administrators at top international schools. As the program grew, the number of countries expanded to include Germany, Italy, England, Denmark, China, Japan, Korea, Thailand, the Philippines, Malaysia, and others.

“My method in going to universities was to make contact with deans and professors,” Rosenberg says. “The theory was that if they got to know us personally, they would talk to their students about the Law School; it established instant credibility, as opposed to me just showing up and handing out leaflets like a salesman.”

His efforts paid off. Guided by his personal approach, the LL.M. program grew dramatically, educating more than 500 foreign lawyers under his leadership. In addition, hundreds of visiting foreign scholars spent time in residence due to the establishment of a visiting scholar program.

Rosenberg’s efforts on behalf of the Law School have not only helped build the school’s global reputation, but he has made many friends as well. For instance, in November 2019, he was in Tokyo, meeting with a number of Japanese judges who had been visiting scholars in a special program he developed 15 years earlier in conjunction with the Japanese Embassy in Washington, D.C.

“When they heard I was retiring, they invited me to Tokyo,” Rosenberg says. “Some prominent judges took me to their Supreme Court and held a party for me. It was a nice surprise.”

Professor Rosenberg credits William & Mary with not only giving him a stable place to develop his interests in the environment, property and international relations, but also for sharpening his law school administrative skills. In 2008, he was named Associate Dean for Academic Affairs, where he handled crucial tasks that included designing the course schedule. He also spent many years as the faculty advisor to the William & Mary Environmental Law and Policy Review. At the university, he also served as president of the Faculty Assembly. In recognition of his many accomplishments as a professor, Rosenberg was awarded the Chancellor Professorship in 2010.

But he is quick to add the many other, less tangible things he has gained over the years. “The Law School gave me a position and the ability to represent the Law School, which made me more than just a professor,” he says. “It permitted me to have access to universities and law schools in many parts of the world.”

But he is quick to add the many other, less tangible things he has gained over the years. “The Law School gave me a position and the ability to represent the Law School, which made me more than just a professor,” he says. “It permitted me to have access to universities and law schools in many parts of the world.”

He is also grateful for long-standing relationships with fellow faculty.

“I think the colleagues I’ve had here, both past and current, have been very congenial and extremely intelligent people from whom I’ve learned greatly,” he says.

Ever the architect, Rosenberg realizes that legal education is constantly changing, but having a sense of institutional identification and commitment to make the Law School better both internally and externally should be a strong part of its mission going forward.

As he greets those new faculty who follow in his footsteps, Rosenberg remembers his own arrival at a time when the Law School was emerging from a weak period in its history with a brand new building and strengthened academic accreditation.

“We came with a strong sense of camaraderie, institutional loyalty and affiliation, and we were building something that we wanted to be really good and respected,” Rosenberg says. “I hope the next group takes the Law School to a new level and to where it should be in the world.”

***

Please consider thanking Professor Rosenberg for his years of service by allocating your gifts and pledges to a new initiative, the Ron Rosenberg LLM Program Fund (4794). Give Now

About William & Mary Law School

Thomas Jefferson founded William & Mary Law School in 1779 to train leaders for the new nation. Now in its third century, America’s oldest law school continues its historic mission of educating citizen lawyers who are prepared both to lead and to serve.